1.9 – Unique Elements of the New Republic

Our Founding Fathers had a basic understanding of human nature that no power should be unchecked. In other words, they understood that if you gave someone power, you needed to have a balancing power in the hands of someone else. Our Founders knew that power should be limited and accountable. Every government official should have to answer for their actions and there must be ways to keep them from acting beyond their authorized power. All experience for thousands of years shows that, in the words of Lord Acton, “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”1 Since government always involves the opportunity to aggrandize, or increase power into the hands of the office holders, it is necessary to limit the opportunities for acquiring power. For that purpose, our Constitution includes checks and balances on the three branches of government, and on the federal government as a whole.

Federalism = VERTICAL Checks & Balances

We can find many nations in the world today that have both a central government and state governments, but the United States was the first to place this intergovernmental relationship of federalism into a formal document with very specific lines of jurisdiction between them. This concept of shared sovereignty, where the national government has certain defined powers and the state governments have certain defined powers, requires a clear understanding of the boundaries and activities at each level of government. Article 1, Sections 8, 9, and 10 set up the specific structures of the relationship. Because many of the Founders were concerned the federal government might grow outside its jurisdiction, the Bill of Rights once again confirmed federal limitations through all ten Amendments including the 9th and 10th Amendments. The federal government is limited to only that which is specifically granted to it in the Constitution (its enumerated or listed and defined powers), and the state governments and the people are to retain all other non-enumerated powers. It is imperative to remember the states created the federal government and not visa-versa.

We can find many nations in the world today that have both a central government and state governments, but the United States was the first to place this intergovernmental relationship of federalism into a formal document with very specific lines of jurisdiction between them. This concept of shared sovereignty, where the national government has certain defined powers and the state governments have certain defined powers, requires a clear understanding of the boundaries and activities at each level of government. Article 1, Sections 8, 9, and 10 set up the specific structures of the relationship. Because many of the Founders were concerned the federal government might grow outside its jurisdiction, the Bill of Rights once again confirmed federal limitations through all ten Amendments including the 9th and 10th Amendments. The federal government is limited to only that which is specifically granted to it in the Constitution (its enumerated or listed and defined powers), and the state governments and the people are to retain all other non-enumerated powers. It is imperative to remember the states created the federal government and not visa-versa.

Federalism, or having simultaneous levels of government, is not a new idea,2 but it is the basis for our American system of government. The Supreme Court even held for many years that being a citizen of a state was different from being a citizen of the nation, and the two carried different legal requirements.3

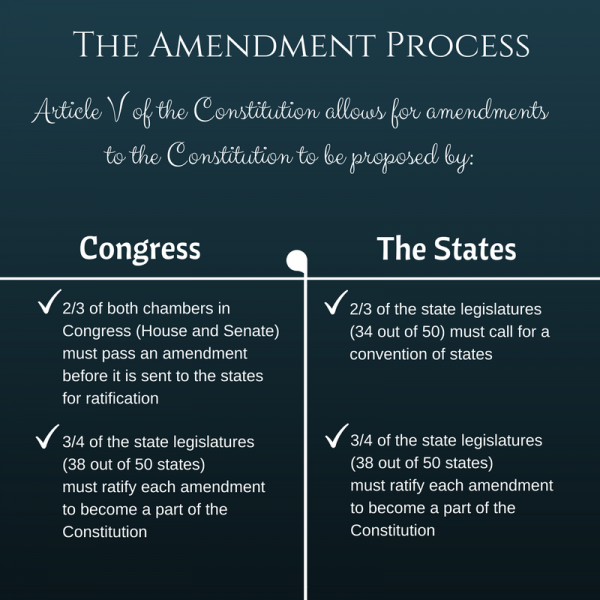

One very important example of how States can keep the power of the federal government limited is the constitutional amendment process. The Constitution itself can only be amended through ratification by the states, so the federal government cannot amend the Constitution to expand federal powers without the permission of states. Article V of the Constitution allows for amendments to be proposed by either Congress or the states, but proposed amendments mean nothing unless three-fourths of the states individually ratify the proposal. Once ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 states would currently have to ratify since we have 50 states), the proposed amendment becomes part of the Constitution.4 This process has been successfully done twenty-seven times which includes the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments). The seventeen other amendments addressed many different issues including prohibiting slavery (13th Amendment), giving women the right to vote (19th Amendment), term limiting the president (22nd Amendment, among others.

Unfortunately, as you will see in Chapters Two and Three, the clear constitutional limitation of the federal government’s powers has been ignored as federal powers have been wrongly expanded through Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution, rather than actual constitutional amendments. The best way for states to reverse this federal power grab and put the federal government back within proper constitutional limitations is to use the amendment process to clarify those limitations, thus over-ruling the Supreme Court’s misinterpretations with clear, actual constitutional language.

Unfortunately, as you will see in Chapters Two and Three, the clear constitutional limitation of the federal government’s powers has been ignored as federal powers have been wrongly expanded through Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution, rather than actual constitutional amendments. The best way for states to reverse this federal power grab and put the federal government back within proper constitutional limitations is to use the amendment process to clarify those limitations, thus over-ruling the Supreme Court’s misinterpretations with clear, actual constitutional language.

The amendment process itself has served our nation well. Since its ratification, our Constitution had been amended twenty-seven times. It’s important to understand that the Constitution is designed to outline the foundations of government and is remarkably brief, just 4,451 words. No other nation can claim this kind of longevity of consistent government or brevity of governing document. For example, France, which had its revolution just one year after our Constitution was ratified, is now on its fifteenth completely new constitution.5

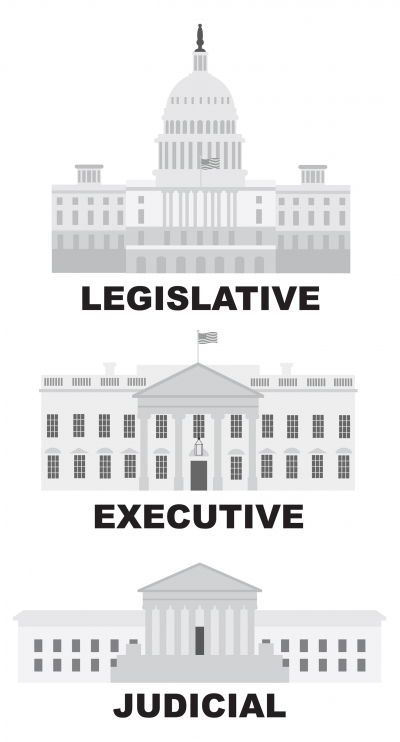

Separation of Powers = HORIZONTAL Checks and Balances

In addition to the states having ways to keep the federal government in check, our Constitution divides federal power into three different branches so there are additional ways to keep that power in check.

For instance, the President cannot make law on his own. He does not even have the power to initiate legislation: that responsibility resides only with the Congress. If both houses of Congress (the Senate and the House of Representatives) agree on a piece of legislation, the President must sign it before it becomes law (unless he chooses to not sign AND not veto, or refuse approval, and just let the bill become a law without his signature). If the President vetoes the legislation, he returns it to the Congress with his reasons for refusal. It then takes a two-thirds vote from both houses to override the veto. So new laws cannot be created unless Congress and the President agree, except in the very rare veto override.

The first time Congress overrode a presidential veto was during the term of President John Tyler, the tenth person to hold that office.6 By then, Presidential vetoes had been successfully used 23 times.7 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, America’s 32nd president, exercised the veto far more than any other president, using it 635 times, which is twenty-five percent of ALL presidential vetoes from all presidents (Congress overrode his vetoes only nine times).8

The overall record shows that the presidential veto is used sparingly (other than FDR), a total of 2,561 times in more than 220 years, with Congress overriding just 110 times. For perspective, that comes out to an average of less than 12 vetoes per year. 9 This suggests that by the time Congress has worked its way through the legislative process, presidents have already been able to have their say in influencing the final legislation, or they are able to accept what Congress has produced (or perhaps in some cases they just realize the futility of politically challenging Congress on that particular issue).

The overall record shows that the presidential veto is used sparingly (other than FDR), a total of 2,561 times in more than 220 years, with Congress overriding just 110 times. For perspective, that comes out to an average of less than 12 vetoes per year. 9 This suggests that by the time Congress has worked its way through the legislative process, presidents have already been able to have their say in influencing the final legislation, or they are able to accept what Congress has produced (or perhaps in some cases they just realize the futility of politically challenging Congress on that particular issue).

Even within the branch of Congress, there are separations of power to limit the abuse of power by any one person or small group of people. For example, only the House of Representatives and not the Senate can begin the process of legislation that will raise money for the federal government (the Founders did this because the Members of the House must return to face the voters every two years and if they spent too much or raised taxes, the voters would be able to remove them from office).

Further checking any legislation even after it gets past the Congress and the President, the Supreme Court, or lower federal courts, can register their opinion on whether or not the legislation violates the plain language of the Constitution. While this system is cumbersome, it serves to slow down any efforts to interfere with the rights of the people.

Another example of checks and balances can be found in the way people are selected for key federal positions. The Congress (both House and Senate) must create agencies and departments, the president then appoints someone to head the agency, and the Senate gets to approve or reject the president’s choice. Further checking the president is the fact that the Congress must pass legislation authorizing the budget for each of those departments.

The Constitution requires that money allocated for the military department cannot be authorized for more than two years at a time. Since the president is Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, this check on his power is a limitation on any military operations he may attempt. Furthermore, the War Powers Act (1973) requires the president to report to Congress within 90 days after sending United States armed forces to a military conflict. After that time period, the president is required to secure congressional approval for the action in order to continue. The Constitution gives only Congress the power to declare war, even though historically the president has frequently directed forces to respond to immediate situations without congressional approval. The War Powers Act is seen by some as a challenge to proper checks and balances of power and is a source of friction that continues even today.10

Even though the president is the head of state, and as such is the primary point of contact with foreign governments, any formal treaty the president arranges with any foreign power or entity must be ratified (approved) by a two-thirds vote in the Senate. In recent history, however, presidents have often used executive agreements, which can have far reaching effects, to conduct limited foreign affairs, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).11 In another example, the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaties (SALT I and II) with Russia have been used to guide military planning even before the Senate has ratified them.12

It took more than a dozen years after the Declaration of Independence was penned to work out the details and learn from trial and error, but the American government created by the Founding Fathers has stood the test of time, producing the most successful nation in recorded history while also allowing for the people to modify the powers and structure of their government when needed.

- John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, Historical Essays & Studies, John Neville Figgis, editor (London: Macmillan and Co., 1907), p. 504, “Appendix” (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=NVk_AAAAYAAJpg=PA505#v=onepage&q&f=false ).

- See, for example, “Federalism,” encyclopedia.com (at: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/us-history/federalism).

- “The governments of the United States and of each of the several states are distinct from one another. The rights of a citizen under one may be quite different from those which he has under the other. To each he owes an allegiance; and, in turn, he is entitled to the protection of each in respect of such rights as fall within its jurisdiction.” Colgate v. Harvey, 296 US 404 – Supreme Court 1935 (at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=colgate+v+harvey&hl=en&as_sdt=6,44&case=3719480264320489813&scilh=0);“We have in our political system a government of the United States and a government of each of the several states. Each one of these governments is distinct from the others, and each has citizens of its own who owe it allegiance, and whose rights, within its jurisdiction, it must protect. The same person may be at the same time a citizen of the United States and a citizen of a state, but his rights of citizenship under one of these governments will be different from those he has under the other.” United States v. Cruikshank, 92 US 542 – Supreme Court 1876 (at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=United+States+v.+Cruikshank+(1876)&hl=en&as_sdt=6,44&case=9699370891451726349&scilh=0); “It is quite clear, then, that there is a citizenship of the United States, and a citizenship of a State, which are distinct from each other, and which depend upon different characteristics or circumstances in the individual.” Slaughter-House Cases, 83 US 36 – Supreme Court 1873 (at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=slaughter+house+cases&hl=en&as_sdt=6,44&case=12565118578780815007&scilh=0); Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 – Supreme Court 1857 (at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?q=dred+scott&hl=en&as_sdt=6,44&case=3231372247892780026&scilh=0).

- “U.S. Constitutional Amendments,” FindLaw (at: https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendments.html) (Accessed on March 31, 2017).

- See https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/la-constitution/les-constitutions-de-la-france

(Accessed on April 29, 2019). - “The First Congressional Override of a Presidential Veto,” United States House of Reprsentatives (at: https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/The-first-congressional-override-of-a-presidential-veto/) (Accessed on March 30, 2017).

- “Presidential Vetoes,” United States House of Representatives (at: https://history.house.gov/Institution/Presidential-Vetoes/Presidential-Vetoes/) (Accessed on March 30, 2017).

- “Presidential Vetoes,” United States House of Representatives (at: https://history.house.gov/Institution/Presidential-Vetoes/Presidential-Vetoes/) (Accessed on March 30, 2017).

- “Presidential Vetoes,” United States House of Representatives (at: https://history.house.gov/Institution/Presidential-Vetoes/Presidential-Vetoes/) (Accessed on March 30, 2017)

- Rober McMahon, “Balance of War Powers: The U.S. President and Congress,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 20, 2011 (at: https://www.cfr.org/united-states/balance-war-powers-us-president-congress/p13092).

- “North American Free Trade Agreement,” Encyclopedia Brittanica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement) (Accessed on March 31, 2017); “NAFTA Signed into Law,” History.com (at: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nafta-signed-into-law) (Accessed on March 31, 2017); James Gerstenzang, “Senate Approves NAFTA on 61-38 Vote,” Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1993 (at: https://articles.latimes.com/1993-11-21/news/mn-59485_1_trade-pact).

- “Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT),”Encyclopedia Brittanica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Strategic-Arms-Limitation-Talks) (Accessed on March 30, 2017).