1.4 – Independence Declared 2.0

Declaring Rights

We once again fast-forward and find ourselves, just a year later, back in Virginia, where, in May of 1776, George Mason, a neighbor of George Washington and a leader in the political discussions in the House of Burgesses, has drafted a series of statements about the inherent rights of men, and the role of good government. The Virginia House accepts these 16 statements on June 12, 1776 as the Virginia Declaration of Rights (see Appendix).1

Just days before on June 7th, Mason’s fellow Virginian, Richard Henry Lee, offered a resolution before the Congress meeting in Philadelphia. The resolution stated that the colonies “are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” After much deliberation, on June 11th the Congress authorized a committee of delegates to draft a declaration of independence.2

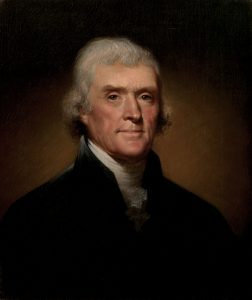

Committee members Benjamin Franklin (PA), John Adams (MA), Robert Livingston (NY) and Roger Sherman (CT) insisted on the fifth member of the committee, Thomas Jefferson (VA), to write the initial draft.3 Jefferson later stated that he did not invent any new ideas, but rather drew on the intentions and writings in broad circulation at the time.4 His discernment in choosing just the right words made it easy for the committee as a whole to edit his draft. Notably, one of the larger changes was the elimination of Jefferson’s denunciation of the slave trade.5 Unanimous support for independence was needed and the delegates from slaveholding colonies refused to support the language lambasting the slave trade. It should be noted that in 1775, some number of slaves were being held in almost all the colonies,6 even though many religious people, including many of the Founding Fathers, denounced the practice and sought abolition.7

The basic concepts of personal and national freedom are carefully spelled out in the Declaration of Independence. These core concepts function as a frame around our freedoms, designed to protect and preserve liberty. Knowledge and understanding of these concepts from their original intent is critical to the continuance of our nation as a sovereign entity among the nations of the world. Unless these concepts are clearly communicated to, and studied by each new generation, our nation will cease to exist in the form on which it was founded.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”8

The Declaration states that the following “truths” are “self-evident,” which means these are universal truths for all peoples and for all times. The Founders began the nation by stating the fundamental truths: (1) there is a God who created us equally, (2) our rights come from God, not government, and (3) government is put in place by the people for the purpose of protecting these God-given rights. We must always remember the Source of these truths and principles is not a document written by man, and certainly not a government, but rather they come from our Creator God. He is also the Source of the “unalienable” (meaning absolute and fixed by God) rights that belong to every individual.9

We clearly see in this section that the role of “governments” is to secure these God-given rights. Governments are not the source of these rights, and any powers governments do obtain are derived first from God and then from the people that are governed…the citizens.

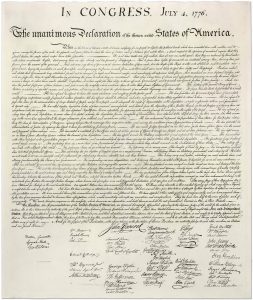

The Declaration of Independence, 1776

Although fighting had begun, it would be another 14 months before the colonists would declare their independence. They still considered themselves British citizens and sought all means possible to settle the conflict without a total break from England. For 11 years (from 1765 until 1776), the Americans worked hard to achieve reconciliation. In fact, even after armed battles had occurred not only in Massachusetts and Virginia but also in New Hampshire and New York, the Americans sent the Olive Branch Petition (1775) to the king, still seeking to peacefully settle their differences. But the king flatly rejected it without even reading it.10

By June 1776, the Continental Congress concluded that a peaceful resolution was not possible. In early July, the delegates spent several days debating whether to become a separate nation, and then in finalizing the wording of the Declaration of Independence. On July 4, 1776, the final wording was officially approved, and a few weeks later, 56 Founding Fathers signed the document. From Great Britain’s perspective, those 56 men were all traitors, making them legally subject to the death penalty.

The Declaration reflects many of the key Christian political principles embraced by America’s Founders in its opening pronouncement:

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness…11

America’s Founders believed that rights came from God; that government must be based on the consent of the governed; and that when governments become tyrannical that they may be resisted and replaced. The document ends by clearly affirming that the patriots had “a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence.”12 Academics and popular authors who contend that the Founders did not believe in God13 must have skipped this line.

Today, too little is known by the general public about those who risked so much. Many Americans no longer know much about their personal stories, occupations, sacrifices, religious faith, or families.

Because of the service they rendered for their country, many patriots were frequently separated from their families, often for long periods and sometimes forever. Among the signers of the Declaration, such is the story of Francis Lewis, who lost his wife at the hands of the British; John Witherspoon, whose son was killed by British soldiers; Richard Stockton, who was made a prisoner of war and was so abused by the British that his life was cut short, leaving his six children fatherless; and John Hart, who was driven by the British from the bedside of his beloved and ailing wife, whom he never saw again. There are many other heart-wrenching accounts.

The care, devotion, and affection so many Founding Fathers had for their family and children is well illustrated by the life of Patrick Henry. This remarkable leader gave much to help secure America’s freedom, and because of his great abilities and leadership, Virginia repeatedly called him to places of public trust. He was elected governor five times, including twice when he was not running.14

After decades of service, Henry declined these positions as he grew older, preferring to spend more time with his family (he had 15 children and 77 grandchildren). Visitors to his home reported finding him “lying on the floor with a group of these little ones climbing over him in every direction, or dancing around him with obstreperous [loud] mirth, to the tune of his violin, while the only contest seemed to be who should make the most noise.”15

A Few Clarifications

Before we dive deeper into the principles in the Declaration upon which the American system of government was founded, two of the Declaration’s phrases need clarification:

First, how could the Founders say all men are created “equal” while maintaining slavery?

Second, what did they mean by the “pursuit of happiness?”

For a discussion regarding slavery and the Founders, watch the following video from the Foundations of Freedom video series and then listen to the audio below from WallBuilders Live!.

Radio Broadcast – Founding Fathers,

Why Did It Take So Long To End Slavery?

Foundations Of Freedom Thursday

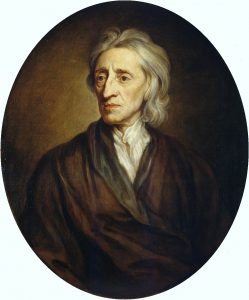

A phrase in the Declaration that often causes confusion is the “pursuit of happiness.” This meant the right to “attempt to secure” or “pursue” happiness, not a guarantee of happiness or a re-distribution of happiness. Jefferson used this phrase from what was a common source of his day. “Pursuit of happiness” was defined and described by John Locke, a major influence on the American Founders, in his Essay on Human Understanding.16

Most people in Jefferson’s day used Locke’s phrase, “life, liberty, and property,” instead of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” At that time, the word “property” meant so much more than land or a home. It included both physical production from labor as well as intellectual property, both of which could bring about happiness. The same ideas can be found in the first section of the Virginia Declaration of Rights.17 Property is defined in Webster’s 1828 dictionary in this way:

“The exclusive right of possessing, enjoying and disposing of a thing; ownership. In the beginning of the world, the Creator gave to man dominion over the earth, over the fish of the sea and the fowls of the air, and over every living thing. This is the foundation of man’s property in the earth and all its productions. Prior occupancy of land and of wild animals gives the possessor the property of them. The labor of inventing, making or producing any thing constitutes one of the highest and most indefeasible titles to property . . . Literary property is the exclusive right of printing, publishing and making profit by one’s own writing.”18

At the time in England, property was owned by the kind and he may or may not decide to share some with the citizens. In this system, the right to pursue happiness through property of all kinds was limited to the king’s approval. The Declaration was doing something new – declaring the God-given right to pursue, acquire, possess, own, use and enjoy one’s own private property. This pursuit was where happiness was to be found.

When agreeing to the use of the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” the delegates to the Continental Congress were saying that true happiness arises from a person’s ability to use property (physical, intellectual, and produced), which is a gift of the Creator.

- Kate Mason Rowland, The Life of George Mason (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1892), Vol. I, Chap. VII (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=5NN4AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA228#v=onepage&q&f=false)

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1860), Vol. VIII, pp. 389, 396 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtki;view=1up;seq=393); Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Government Printing Offce, 1906), Vol. V, pp. 425, 431 (at: https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=005/lljc005.db&recNum=9).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1860), Vol. VIII, p. 396 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtki;view=1up;seq=396). See also “Declaration Independence: Drafting the Documents,” Library of Congress (at: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/declara/declara3.html).

- Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, H. A. Washington, editor (Washington, DC: Taylor & Maury, 1854), Vol. VII, pp. 304-305, to James Madison on August 30, 1823 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=k2MSAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA304#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- See, for example, “The Declaration of Indenpendence: Compare,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/document/compare.html).

- “Stories From The Revolution,” www.nps.gov (at: https://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/african_americans.html); George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1860), Vol. IX, p. 448 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044097892558;view=1up;seq=458)

- “The Founding Fathers and Slavery,” wallbuilders.com (at:https://wallbuilders.com/founding-fathers-slavery/).

- Editors’ Note Many early American quotes have been inserted throughout this text – historical quotes made at a time when grammatical usage and spelling were quite different from what is practiced today. In an effort to improve readability and flow, we have modernized spellings and punctuation in those quotes, leaving the meaning unimpaired. As an example of the early colonial spelling of words, consider the opening language of the Pilgrims’ “Mayflower Compact” of 1620 – the first written document of governance in America (the words misspelled by today’s standards are underlined): “We whose names are underwriten, the loyall subjects of our dread soveraigne Lord King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britaine, Franc, & Ireland king, defender of the faith, &c., haveing undertaken, for the glorie of God, and advancemente of the Christian faith, and honour of our king & countrie, a voyage to plant the first colonie in the Northerne parts of Virginia, doe by these presents solemnly & mutualy in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant & combine our selves togeather into a civill body politick . . .”1 Similarly distracting to today’s readers is the early use of capitals and commas (refer to the previous example for the copious use of commas); to see the excessive use of capitals, notice this excerpt from a 1749 letter written by signer of the Declaration of Independence Robert Treat Paine (underlined words would not be capitalized today): “I Believe the Bible to be the written word of God & to Contain in it the whole Rule of Faith & manners; I consent to the Assemblys Shorter Chatachism as being Agreable to the Reveal’d Will of God & to contain in it the Doctrines that are According to Godliness. I have for some time had a desire to attend upon the Lords Supper and to Come to that divine Institution of a Dying Redeemer, And I trust I’m now convinced that it is my Duty Openly to profess him least he be ashamed to own me An Other day; I humbly therefore desire that you would receive me into your Communion & Fellowship, & I beg your Prayers for me that Grace may be carried on in my soul to Perfection, & that I may live answerable to the Profession I now make which (God Assisting) I purpose to be the main End of all my Actions.”2 To improve readability, the modern rules of spelling, capitalization, and punctuation have been followed in the quotes throughout this book. None of these changes will alter the meaning, and by referring to the sources in the footnotes, the reader will be able to examine the original. Finally, the General Editor personally chooses to capitalize all nouns or pronouns referring to the Bible or Biblical Deity as a sign of his personal respect; and for exactly the opposite reason he chooses not to capitalize words such as satan, lucifer, or the devil. 1. William Bradford, The History of the Plymouth Plantation (Boston: Privately Printed, 1856), pp. 89-90. 2. Robert Treat Paine, The Papers of Robert Treat Paine, Stephen T. Riley and Edward W. Hanson, editors (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1992), Vol. I, pp. 48-49, Robert Treat Paine’s Confession of Faith, 1749.

- For Founding Father quotes on unalienable rights see: John Dickinson, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, R. T. H. Halsey, editor (New York: The Outlook Company, 1903), p. xlii, letter to the Society of Fort St. David’s, 1768 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=uzMSAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR42#v=onepage&q&f=false); Alexander Hamilton, The Works of Alexander Hamilton, John C. Hamilton, editor (New York: John F. Trow, 1850), Vol. II, p. 80, “The Farmer Refuted,” February 5, 1775 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=VJYoAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA80#v=onepage&q&f=false); Samuel Adams, The Life and Public Service of Samuel Adams, William V. Wells, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1865), Vol. I, p. 502, from “The Rights Of The Colonists, A List of Violations Of Rights and A Letter Of Correspondence, Adopted by the Town of Boston, November 20, 1772” (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=XHs-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA502#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1860), 8:130-132.

- See, “In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration By the Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress Assembled,” The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America; The Declaration of Independence; The Articles of Confederation Between the Said States(Boston: Norman and Bowen, 1785), 167-171.

- See, “In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration By the Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress Assembled,” The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America; The Declaration of Independence; The Articles of Confederation Between the Said States(Boston: Norman and Bowen, 1785), 167-171.

- Mark David Hall identifies a number of those who make this claim in his book, Did America Have a Christian Founding? Separating Modern Myth from Historical Truth (Nashville: Nelson Books, 2019), 23-55.

- Under Virginia’s new 1776 state constitution, both houses of the legislature selected the governor. The legislature chose Henry to be governor five times, but the later selections he declined due to increasing age, declining health, and a growing desire to home with his family.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 380-381.

- John Locke, Samuel Pufendorf, and Hugo Grotius all discussed the importance of property: (Andrew P. Morris, “Europe Meets America: Property Rights in the New World,” Foundation for Economic Freedom, January 1, 2007, at: https://www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/europe-meets-america-property-rights-in-the-new-world/#axzz2hulKeDO0). The Founders themselves espoused the same view, such as in John Adams’ 1765 essay “A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law,” and Thomas Jefferson’s 1774 “A Summary View of the Rights of British America;” and others.

- See state constitutions such as: The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia (Richmond: Thomas Ritchie, 1819), Vol. I, p. 31, 1776 Constitution: Declaration of Rights, Art. I (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=VVhRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA31#v=onepage&q&f=false); The Constitutions of the United States, According to the Latest Amendments (Philadelphia: Robert Campbell, 1800), p. 5, 1792 New Hampshire Constitution: Bill of Rights # 2; pp. 34, 1780 Massachusetts Constitution: Declaration of Rights, Art. I; p. 114, 1790 Pennsylvania Constitution: Declaration of Rights # 1; p. 210, 1793 Vermont Constitution: Declaration of Rights, Art. I; p. 121, 1792 Delaware Constitution: Preface (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=_to0AAAAIAAJ&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- “Property,” Webster’s 1828 Dictionary – Online Edition (at: https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/property).