1.1 – The Dawning of Independence 2.0

Before reading about the conflicts that led to America forming a new government, watch the following episode of Chasing American Legends for a better understanding of why leaders like George Washington responded as they did.

The Friction Begins…

Fast-forward to 1763 and we find The Treaty of Paris ending The French and Indian War.1 This conflict between the French and the British was known outside of the colonies as the 7 Years’ War. Although Indian tribes fought on both sides of the conflict, the people in the colonies names the war after who they were fighting – the French and certain Indian tribes allied with the French.

With the French defeat, the British won possession of all former French claims in North America, which went westward from the colonies along the east coast to the mighty Mississippi River, north into Canada, and then south to the Gulf of Mexico.2 Though this land gain should have opened up the entire eastern half of the continent to the American colonists, the British drew a line in the sand for settlements at the Appalachian Mountains. Settlers were not to go beyond this line to the west. They set these boundaries because their military forces were spread too thin to protect settlers from probable Indian troubles.3 But this boundary line did not sit well with the expansion-minded colonists who saw many opportunities on the west side of the Appalachians. In fact, we will find a steady stream of frontiersmen ignoring the Appalachian Mountain line and setting up camps along the Ohio River Valley.

Prior to the French and Indian War, the British Parliament began levying restrictions on the colonies through Navigation Laws that required British ships to carry all commerce to and from the colonies.4 These Navigation Laws were designed to keep the profit of trading within the British Empire and resulted in Americans losing out on a lot of potential profit to the British. In essence, the Navigation Laws were a government controlled monopoly that went completely against the free market principles that the colonists believed in. At the end of the war, the Parliament needed to refill its depleted royal treasury. In early 1764, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer (the head of the royal treasury) presented his American Revenue Act, known on our side of the ocean as the Sugar Act. This Act increased taxes on a large number of commodities, and even banned the importation of certain products, such as French wines and rum. These taxes, done without any input from the colonists, were a source of great frustration. Then, adding to the colonists’ anxiety, was an act to revitalize the royal customs collections service, which was only collecting about a quarter of what it needed to operate.5 This fact resulted in deficits that the British government wanted to fix. To add insult to injury, the Parliament came to the conclusion that the colonials should bear the lion’s share of the cost to keep military forces in the colonies.6 This sparked even more outrage due to the fact that the colonists, with their local militias, did not see a need for these British troops. The colonists were largely used to maintaining their own defense through their local militias.

Without representation in Parliament, the colonists strongly opposed all of these measures and began the mantra of “no taxation without representation.”7 In response to these new edicts, the Massachusetts colonial legislature established a Committee of Correspondence and invited the other colonies to join with them. These Committees of Correspondence were designed to educate the colonists and promote communication throughout the colonies. Through this exchange of information, they were able to protest the new restrictions, taxes, and injustices by beginning a series of boycotts of selected English goods.8

The courts became another sore spot for the colonists when the British Parliament established a new vice-admiralty court, located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to have jurisdiction over all the American colonies. The system was full of grave injustices, such as, all cases were to be tried at this one location, before a panel of military officers instead of a jury of peers; the accused person was required to prove innocence rather than the government prove guilt; and the accused had to post bond to pay for costs of litigation.9 So many of these things end up being specific complaints of the American Founders in the Declaration of Independence and then they specifically prevent these abuses in the American Constitution. But just wait! The list gets longer.

1765 brought even more agitation as Parliament passed two more egregious acts affecting the colonies. First, the Quartering Act, which required the colonists to provide supplies and housing for the British troops in public buildings, private buildings, and even private homes.10 Second, the Stamp Act, which had nothing to do with postage stamps, required all paper documents to carry a special stamp showing that a tax was paid on the items. Because this tax applied to every legal document, newspaper, almanac, and shipping document, even playing cards, its economic impact was felt in every colony at every level.11

Colonists Begin to Push Back

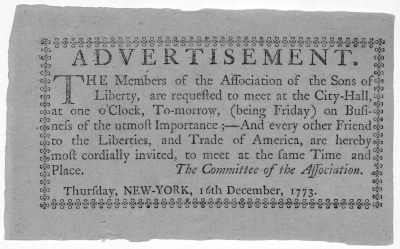

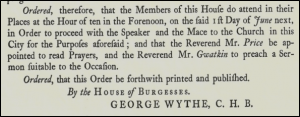

Secret organizations arose in many communities, often using the name “The Sons of Liberty,” to challenge enforcement of the new laws.12 Tax collectors were sometimes harassed until they resigned their official positions, some were tarred and feathered, and even homes of a few government officials were ransacked.13 Boycotts of English goods were organized through the strong communication lines that were the Committees of Correspondence, and encouraged by many prominent leaders in Massachusetts and resolutions written by Virginian Patrick Henry were narrowly adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses.14 The backlash from the colonies forced the government in England to take action. The Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, largely at the insistence of British merchants hurt by the boycotts. However, its repeal was followed the same day by the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had “binding authority” (absolute power) over the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”15 Obviously, this restriction of colonial autonomy was yet another straw on the camel’s back that was getting ready to break.

Secret organizations arose in many communities, often using the name “The Sons of Liberty,” to challenge enforcement of the new laws.12 Tax collectors were sometimes harassed until they resigned their official positions, some were tarred and feathered, and even homes of a few government officials were ransacked.13 Boycotts of English goods were organized through the strong communication lines that were the Committees of Correspondence, and encouraged by many prominent leaders in Massachusetts and resolutions written by Virginian Patrick Henry were narrowly adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses.14 The backlash from the colonies forced the government in England to take action. The Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, largely at the insistence of British merchants hurt by the boycotts. However, its repeal was followed the same day by the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had “binding authority” (absolute power) over the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”15 Obviously, this restriction of colonial autonomy was yet another straw on the camel’s back that was getting ready to break.

In 1767, Charles Townshend became the new British Chancellor of the Exchequer. After he got the Parliament to pass legislation reducing land taxes in England, he immediately asked the Parliament to pass laws aimed at shifting the tax burden to the colonies. Known as the Townshend Acts, he asked for new duties (taxes) on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea imported into the colonies. He also abused his authority by allowing customs officials to issue writs of assistance.16 What is a writ of assistance? It allowed local judges to issue open-ended search warrants that did not specify the objects or places of the search and the writs never expired.17 These writs of assistance were especially egregious to the colonists. Officials could go into any home or business, anytime they wished, and search for anything they wanted. For example, John Hancock’s merchant ship, the Liberty, off-loaded a cargo of wine without paying customs, and was then seized by the British navy using one of these writs of assistance.18

As these usurpations continued, customs officials began formally requesting troops be quartered in Boston for their own protection.19 Pressure continued to mount when the New York Colony’s boycott of British goods resulted in minor riots in that city. When the New York colonial legislature refused to pay for the quartering of British troops, the London Board of Trade, which still supervised all activity in the American colonies, declared all acts of the NY legislature null and void.20

As we move two years forward in this historic timeline, 1769 proved to be a pivotal year in the colonies. Tensions were so high between the colonists and British officials that the Virginia House of Burgesses (the state legislature for Virginia) unanimously adopted resolutions declaring the sole right to tax the colonists lay with the governor and legislatures of each colony. The resolutions also included condemnation of the proposal that “American” troublemakers be tried in England, demanding they be tried in the colony in which they reside. The names affixed read like a Who’s Who among American Founders (George Washington, Patrick Henry, George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, Carter Braxton, Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, and many others).21 The royal governor immediately dissolved the Virginia assembly.22 How did the colonists respond? Other colonies’ legislatures followed Virginia’s lead with resolutions of their own.23 And this would not be the last time that British authorities unilaterally dissolved American elected assemblies. These actions led to increased boycotts of British goods across the colonies. In fact, New York decreased import of British goods by almost eighty-five percent.24 The response from England’s new Prime Minister, Lord Frederick North, was to repeal almost all of the import duties/taxes. But in an effort to remind the colonists that Parliament still had authority “in all cases whatsoever,” he kept the tax on tea.25

Bloodshed Begins…

Although the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, the British did not want the Americans to believe they were free from British control so they passed the Declaratory Act, affirming that Britain had authority to make laws binding colonists “in all cases whatsoever.”26 To many patriots, the idea of such unlimited power was the very definition of tyranny.

Britain then passed the Townshend Acts (1767), which placed additional taxes on common items they would import from Britain. But from the American’s viewpoint, they were still wrong, for they had been passed without any American consent or representation.

One of the patriots who led the opposition to these new measures was John Dickinson, who later became a member of the first Continental Congresses and went on to become a signer of the Constitution. He wrote articles rebutting the Townshend Acts, arguing that America should be in charge of its own internal and domestic affairs. His writings were widely distributed throughout the 13 colonies and helped inspire the growth of resistance. Dickinson became known as the “Penman of the Revolution.”27

Samuel Adams authored the official response of the Massachusetts legislature, calling the Acts a violation of the “natural and constitutional rights” of Americans28 (what the Declaration of Independence later called “inalienable rights”). That document urged a return to the principle of local control of taxation and called for the other states to boycott the newly taxed goods.

British officials ordered Massachusetts to retract its response, but by a 92-17 vote, the legislature rejected that demand.29Crown-appointed Governor Francis Bernard then dissolved the legislature, resulting in widespread protests from citizens. The British sent several regiments of soldiers to Boston, believing this show of force would quell tensions, but it had the opposite effect.

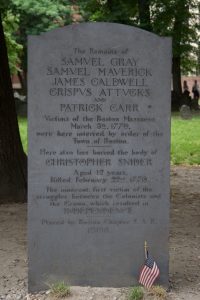

In March of 1770 a British soldier on patrol along King Street in Boston heard a young American insult his British officer and the soldier smacked him in the head with his musket. When the boy cried out in pain, citizens rushed to investigate. Tempers mounted and insults were exchanged. The growing crowd began to throw rocks at the soldier, daring him to shoot them. When word of the altercation reached British Captain Thomas Preston, he dispatched several soldiers, who ran toward the crowd with fixed bayonets, forming a defensive line and barking orders at the assembly.

One of the frustrated crowd members tired of the oppressive British behavior was Crispus Attucks.

Few records exist about his birth or early life, but it is believed that he was an escaped slave who

became a sailor. He likely had a shared Native American and African American ancestry, but today Attucks is celebrated as a black patriot who firmly opposed British tyranny.

The crowd, then several hundred, continued to yell at the soldiers, and many began throwing snowballs and rocks; some even approached the soldiers with clubs. One soldier, struck by a thrown stick, angrily fired into the crowd. Other soldiers, fearful for their own safety, joined him and fired a volley. Three colonists were killed instantly, with eight others wounded, two of whom died shortly thereafter. Crispus Attucks was one who died during the volley and his blood was regarded as the first spilled in the cause of liberty.30 Paul Revere produced an engraving of this event, which became known as the “Boston Massacre,” and subsequent images featuring Attucks were printed across the decades.

Prominent attorney John Adams was chosen as the defense attorney for the British soldiers,31 who had been arrested and accused of murder. Even though Adams was an ardent patriot, his integrity and zeal for justice and the law were uncompromised. He honorably and ably represented the soldiers, and the charges were dropped against most. For two soldiers, the charge was reduced from murder to manslaughter, for there had been no initial intent to kill and they were primarily responding in fear for their lives.

This deadly event seemed to cement the course of the coming conflict. The relationship between the Americans and the British continued to deteriorate. John Adams, speaking of the Boston Massacre, later acknowledged:

Not the battle of Lexington or Bunker Hill, not the surrender of Burgoyne or Cornwallis were more important events in American history than the battle of King Street on March 5th 1770.32

Another incident of hostility followed in June 1772. A British customs ship, the HMS Gaspee, was in pursuit of a probable smuggler ship (a free merchant ship that was not following the British Navigation Laws) in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. The smugglers appeared to deliberately lead the customs vessel into shallow waters where it ran aground. That night, several boatloads of “unknown persons” completely destroyed the ship by setting it on fire. Upon investigation of the Gaspee Incident, the British found no one willing to admit to having any information whatsoever. The British reacted to the silence by announcing that anyone involved in the incident would be tried in England, and henceforth, all judges would be paid directly from the British treasury and not from local taxes.33 This would mean no local accountability for judges, which colonists knew was a formula for abuse.

The Gaspee Incident also brought about a resurgence of the Committees of Correspondence for disseminating important information about British abuses of power throughout the colonies.34 This relatively good communication network had the effect of unifying the colonies in a new way.

The Committees of Correspondence, 1772

As noted earlier, in the years leading up to the War for Independence the 13 colonies had been highly independent from each other. There was therefore no consistent system of communication between them. But when the tensions between Britain and America first began to escalate in 1766, the Rev. Jonathan Mayhew of Massachusetts proposed the use of circular letters to begin uniting the colonies in thinking and action.35 He died before his proposal could be fully implemented, but his idea was eventually brought to reality in 1772 by Samuel Adams, the “Father of the American Revolution.”

Adams believed that the British government had violated the colonists’ rights as individuals, citizens, and Christians. The conflict between the colonies and England therefore was not just political and economic but also spiritual. Adams understood that a knowledge of their rights in each of these three areas must be known and appreciated.

To help achieve this unity of ideas and principles, Adams proposed that “Committees of Correspondence” be established in every colony.36 Each would set up communication with the others, reporting to the rest what was occurring in their state. They would also provide materials that could be shared to help educate and alert citizens in every colony to the common principles for which they were all fighting, and the actions each should take.

Many responded enthusiastically to Adams’ proposal. However, one patriot who supported the effort nevertheless lamented that some might not join because “they are dead and the dead can’t be raised without a miracle.”37 But Adams disagreed, replying, “All are not dead, and where there is a spark of patriotic fire, we will enkindle it.”38

Sam Adams’ plan moved forward, and he personally wrote the first circular letter. It clearly set forth the Biblical basis of their endeavors, calling on Americans to study “the institutes of the great Law Giver and Head of the Christian Church, which are to be found clearly written and promulgated in the New Testament.”39

It is not surprising that Adams should say this, for like most of the Founding Fathers, he was a strong Christian, openly declaring “I…[rely] upon the merits of Jesus Christ for a pardon of all my sins.”40 Famous historian George Bancroft further affirmed:

[Samuel] Adams….was a member of the church….Evening and morning, his house was a house of prayer; and no one more revered the Christian Sabbath. The austere purity of his life witnessed the sincerity of his profession [of Christianity].41

As the flames of discontent and a desire for freedom continued to rise in the colonies, the East India Company (the British merchant consortium responsible for trade with the new British colony in India) was in serious financial trouble because of the American boycotts on tea. In May of 1773, with seventeen million pounds of tea in English storehouses and little market for it, the East India Company convinced Parliament to remove duties on tea in the home country of England, but leave a tax of three pence per pound of tea on the American colonies.42

The Americans detested this interference with free trade. Since many colonists considered themselves full Englishmen, this blatant favoritism to England at the expense of the American colonies was considered yet another injustice toward the colonists.

The Original Tea Party, 1773

Massachusetts, having not only had its legislature dissolved but its citizens shot down in the Boston Massacre, closed it ports to British trade ships. The British Parliament responded by repealing portions of the Townshend Acts, eventually repealing all the taxes except that on tea, one of the most popular drinks in America. The Americans continued to object to being taxed without their input, so they simply refused to buy any tea upon which the tax had been placed. As tea sales plummeted, tea began to pile up in warehouses in England. Tea merchants asked the British government to intervene, and without opposition Parliament voted to subsidize (that is, underwrite) the cost of the tea by lowering its price and making it cheaper than any tea that Americans could purchase elsewhere, even through smuggling.43 Although the tea act slashed the price, Great Britain still kept the previous tax on the tea, believing the colonists would surely buy it (and thus pay the tax) if it were cheaper than the other alternatives. Benjamin Franklin knew better. He pointed out that the Americans objected to the principle of unjust taxation, not the price of the tea; so even if the tea were cheap but still had the tax, the Americans would stand by their principles and not buy it.44 He was right: Americans refused to purchase even the inexpensive tea.

Infuriated, Britain decided to force the Americans to buy it. As early historian John Fiske reported, “Lord North [the British Prime Minister] said, it was of no use for anyone to offer objections, for the king would have it so.”45 The tea was ordered sent to America—Americans would pay for it and there would be no opt outs.

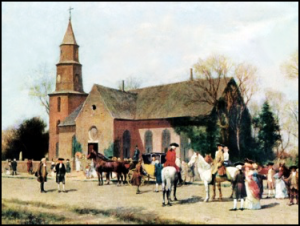

The patriots in the seaports where the tea ships were scheduled to arrive held town meetings to decide what to do. When one tea ship docked in Boston, the patriots put guards on the craft; its tea was not to be unloaded. But that decision put the ship’s owner, Joseph Rotch, in a very difficult situation. He wanted to explain his dilemma to the Americans, so patriot leaders called for a public meeting at Boston’s Old South Meeting House. Approximately 7,000 citizens came to hear him.46 He told the crowd that if he attempted to sail back to England without unloading the tea, his business, and perhaps even his life would be in danger, for the British had threatened to seize and confiscate his ships unless the tea was offloaded by a certain date.

The colonists sympathized with his predicament and came up with a solution to deal with the hard-fisted British policy and at the same time protect Rotch’s business. The Americans would board the ship and throw the tea overboard; the ship could therefore return to England without the tea. But at the same time, the Americans still would not be compromising their principles by accepting the tea. In their eyes, it would be a win-win situation.47

To protect those boarding the ship from British reprisals, they disguised themselves as Indians. Early historian Richard Frothingham reported:

The party in disguise…whooping like Indians, went on board the vessels; and warning their officers and those of the customhouse to keep out of the way, unlaid the hatches, hoisted the chests of tea on deck, cut them open, and hove [dumped] the tea overboard. They proved quiet and systematic workers. No one interfered with them. No other property was injured; no person was harmed; no tea was allowed to be carried away; and the silence of the crowd on shore was such that the breaking of the chests was distinctly heard by them. “The whole,” [Governor] Hutchinson wrote, “was done with very little tumult.”48

This event, which occurred on December 16, 1773, became known as the “Boston Tea Party.” Similar but less famous “tea parties” were also held in other cities, including Philadelphia, Charleston, New York, and Annapolis.49

The Intolerable Acts, 1774

When word of what the colonists had done arrived back in Great Britain, members of Parliament and the King were furious. They retaliated by passing a series of acts that they referred to as “The Coercive Acts” but which Americans called “The Intolerable Acts.” Among them was the Boston Port Act, which stipulated that beginning on June 1, 1774 the British Navy would blockade and completely close down the harbor in Boston, thus shutting off all commerce to and from one of America’s busiest seaports. This act was intended to cut off the Bostonians’ supplies and starve the townspeople into submission.50

When Boston’s Committees of Correspondence informed the other colonies what was happening, wagonloads of food and supplies began rolling in from across the country.51 Furthermore, throughout the state:

The day was widely observed as a day of fasting and prayer. The manifestations of sympathy were general. Business was suspended. Bells were muffled and tolled from morning to night; flags were kept at half-mast; streets were dressed in mourning; public buildings and shops were draped in black; large congregations filled the churches.52

Virginia joined Massachusetts, in calling a day of prayer. Thomas Jefferson was among those who penned Virginia’s state prayer resolve, which called on the legislature and the people “to implore the Divine Interposition…to give us one heart and one mind firmly to oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American rights.”53 On the designated day:

The members of the [Virginia] House of Burgesses assembled at their place of meeting and went in procession—with the speaker at their head—to the church and listened to a discourse [sermon]. “Never,” a lady wrote, “since my residence in Virginia have I seen so large a congregation as was this day assembled to hear Divine service.” The preacher selected for his text the words: “Be strong and of good courage, fear not, nor be afraid of them; for the Lord thy God, He it is that doth go with thee. He will not fail thee nor forsake thee [Deuteronomy 31:6].” “The people,” Jefferson says, “met generally with anxiety and alarm in their countenances [their faces], and the effect of the day through the whole colony was like a shock of electricity, arousing every man and placing him erect and solidly on his center.” These words describe the effect of the Port Act throughout the 13 colonies.54

The Intolerable Acts united the colonists and encouraged them to work together to protect their rights. John Adams spoke of the miraculous nature of this new unity, explaining: “Thirteen clocks were made to strike together, a perfection of mechanism which no artist had ever before effected.”55 (An old clock shop filled with various wind-up clocks never sounds all the bells and chimes in unison; but this time it was different.)

This external union of the colonies came about because of the internal unity of ideas and core Biblical principles sown into the hearts of the American people by its leaders, families, schools, and churches. The Latin phrase on our National Seal reflects this Christian union: E Pluribus Unum—”out of many, comes one.”

This was soon followed by the Massachusetts Government Act, which basically annulled the colonial charter, leaving the royal appointed governor in complete control of the legislature, law enforcement, and judiciary.56 As a result, the people and the colonial elected officials completely lost their voice in public policy matters.

The new Quartering Act was parliament’s next move, authorizing quartering British troops in private, occupied homes of average citizens. (Just imagine the government forcing your family to open your home to strange men, agents of a government antagonistic to your family, and sleeping and eating under your roof.)57 How much resentment do you think this would build up in your family?

Parliament then passed the Quebec Act, which defined Canada’s boundaries as extending southward to the Ohio River. This was intolerable to the people of Virginia, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, all of whom had claims to parts of the Ohio River Valley.58

Next move, Virginia. A small group of delegates to the House of Burgesses, including Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and Richard Henry Lee, met to discuss the public apathy about their deteriorating freedoms. They agreed to call for a day of prayer, humiliation and fasting before God, and sent letters to all the colonial Committees of Correspondence, asking them to join in this public expression of faith. Thomas Jefferson penned the resolve in Virginia “to implore the Divine Interposition…to give us one heart and one mind firmly to oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American rights.”59

What day did they choose to fast and pray? The day the Boston Port Bill was to go into effect!60

The First Continental Congress, 1774

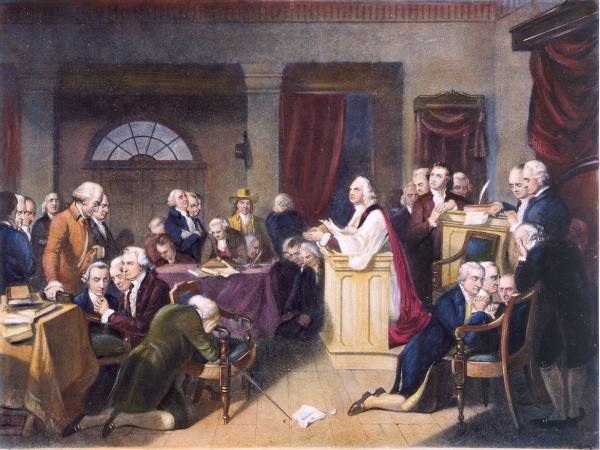

Evidence of America’s new unity became apparent when our first national assembly met in September, 1774. Forty-five delegates from across the colonies gathered in Philadelphia in what became known as the First Continental Congress. Each was a significant figure in his own area, but largely unknown to those in the other colonies.

As they met to contemplate their course of action, John Adams reported:

When the Congress first met, Mr. [Thomas] Cushing [of Massachusetts] first made a motion that it should be opened with prayer.61

This apparently harmless suggestion of beginning that meeting with prayer was met by surprisingly stiff resistance:

It was opposed by Mr. [John] Jay of New York and Mr. [John] Rutledge of South Carolina because we were so divided in religious sentiments – some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Anabaptists, some Presbyterians, and some Congregationalists – that we could not join in the same act of worship.62

Strikingly, Jay and Rutledge were pious Christians. In fact, Jay became a founder and president of the American Bible Society and wrote lengthy treatises on Christianity and theology.63 Both he and Rutledge were Anglicans, but they knew that many of the other delegates were of different denominations. They worried that inviting a member of the clergy from one denomination would be opposed by members of the others.

But Samuel Adams turned things completely around. He took the message of Whitefield’s popular “Father Abraham” sermon and gave it practical application. After hearing Jay and Rutledge oppose the motion to pray together, Adams “arose and said he was no bigot, and could hear a prayer from a gentleman of piety and virtue, who was at the same time a friend to his country.”64 He then acknowledged that because he was from Boston

he was a stranger in Philadelphia, but had heard that [the Rev.] Mr. [Jacob] Duché deserved that character, and therefore he moved that Mr. Duché, an Episcopalian clergyman, might be desired to read prayers in the established form to the Congress tomorrow morning.65

Samuel Adams, an ardent Congregationalist, personally recommended having an Episcopalian, which at that time meant an Anglican clergyman from the Church of England (a denomination intensely disliked by Sam Adams’ Congregationalists) deliver the first opening prayer in Congress. By this suggestion, Adams was implementing the Biblical message of Acts 10:35 preached for so long by Whitefield in his “Father Abraham” sermon. His Whitefield-like suggestion penetrated the hearts of the other delegates:

[Cushing’s] motion was seconded and passed in the affirmative. Mr. [Peyton] Randolph [of Virginia], our President, waited on Mr. Duché….Accordingly, next morning he [Mr. Duché] appeared with his clerk and in his pontificals [robe worn by high-church clergy during services].66

But Duché, rather than solely following the traditional Anglican formality of reading from the Book of Common Prayer, additionally launched into an unforeseen, passionate, and spontaneous prayer,67 surprising everyone present. He also spent time reading Psalm 35. What was the impact? According to John Adams:

I never saw a greater effect upon an audience. It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that [35th] Psalm to be read on that morning. After this, Mr. Duché, unexpected to everybody, struck out into an extemporary [spontaneous heartfelt] prayer which filled the bosom of every man present. I must confess I never heard a better prayer…with such fervor, such ardor [passion], such earnestness and pathos [emotion], and in language so elegant and sublime, for America, for the Congress, for the province of Massachusetts Bay, and especially the town of Boston. It has had an excellent effect upon everybody here.68

Several delegates likewise commented favorably on Duché’s remarkable prayer, including Samuel Adams,69 Joseph Reed,70 Samuel Ward,71 and others. For example, Silas Deane reported that the prayer not only was “worth riding one hundred mile to hear”72 (about three days in the saddle) but that it was so powerful even the stern Quakers (a group frequently harassed by Duché’s Anglican denomination) “shed tears” as they listened to it.73

Deane further noted that “the lessons [Scriptures] of the day were accidentally extremely applicable.”74 John Adams agreed, affirming that the reading of Psalm 35 on that day, with its opening line “Plead my cause, O Lord, with them that strive with me: fight against them that fight against me” was not only “most admirably adapted” but also that is was “Providential.”75

Significantly, when the Book of Common Prayer had been written in 1662 under King Charles II, Psalm 35 was designated for reading on September 7 of each year (other passages assigned for that day and studied in Congress that morning included Amos 9, Matthew 8, and Psalm 36). The fact that Psalm 35 had been attached to that particular day well over a century earlier affirmed to the Founders that God indeed had known what they would be facing at that time, thus confirming to them that He was watching over them.

The “Father Abraham” sermon so often preached by Whitefield encouraging unity among Christians was put into practical effect at the First Congress. It changed the atmosphere from one of distrust and disagreement into one of understanding and cooperation. The walls between them were being knocked down. In fact, 70 years later, the great Daniel Webster, often referred to as the “Defender of the Constitution,” reminded the US Supreme Court of the Christian unity manifested on that morning:

At the meeting of the first Congress, there was a doubt in the minds of many about the propriety of opening the session with prayer; and the reason assigned was, as here, the great diversity of opinion and religious belief. Until at last Mr. Samuel Adams, with his gray hairs hanging about his shoulders and with an impressive venerableness now seldom to be met with…rose in that assembly, and with the air of a perfect Puritan said it did not become men professing to be Christian men who had come together for solemn deliberation in the hour of their extremity to say that there was so wide a difference in their religious belief that they could not, as one man, bow the knee in prayer to the Almighty, Whose advice and assistance they hoped to obtain….And depend upon it, that where there is a spirit of Christianity, there is a spirit which rises above form, above ceremonies, independent of sect or creed, and the controversies of clashing doctrines.76

Applying the message of the “Father Abraham” sermon produced the unification between the colonies that would be necessary for them to withstand the intense conflict soon to begin.

But there was still more. John also told Abigail that, “We [Congress] have appointed a Continental fast. Millions will be upon their knees at once, before their Great Creator, imploring His forgiveness and blessings—His smiles on American councils and arms.”77 This was the first of 15 times that Congress issued official national calls to prayer throughout the conflict.78

We discover that 1774 brought a shift in action throughout the colonies. That summer, twelve of the colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress.79 This gathering was the first significant join national assembly with many of the same men who would later lead in the birth of the new nation. Unsurprisingly, they began the historic gathering with an extended time of prayer and Bible study. Congress then passed several resolutions directed to the colonists in which they: (1) condemned what they called Coercive Acts of Parliament (the group name for all of the recent acts that Parliament had passed to restrict and punish the colonies, also called the Intolerable Acts) as intolerable, and therefore not to be obeyed; (2) urged the people of Massachusetts to form a government to collect taxes, but withhold them from the royal governor until the Coercive Acts were repealed; (3) advised the people throughout the colonies to form armed militias for their own protection; and (4) recommended increased restrictions on trade with England.80

This First Continental Congress also passed two other resolutions directed to the king. They first protested the Quebec Act as unjust. Among other things, this Act expanded the territory of Quebec into what was previously Ohio territory, restored the limited use of French civil law in private law, and restored the Catholic Church’s ability to forcefully impose tithes.

Later, in the Declaration of Independence, the colonists would enumerate their problems with the Quebec Act by saying that it was “…abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies…”

The second resolution passed by Congress petitioned the king to end the Coercive Acts; but the American colonists still pledged loyalty to him.81 It is hard for us to imagine it today, but at that time, we must understand that a vast majority of colonists still considered themselves loyal subjects to the king. Many believed he was only being misled by his court and parliament. The Congress decided to meet again in May, 1775, if the response from Britain was not acceptable.82

The British response was mixed at best. The Prime Minister, Lord North, introduced legislation in the House of Lords calling for official recognition of the Continental Congress, granting it limited powers to set taxes in the colonies, but the Parliament rejected his plan. Instead, it officially declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion.83 A month later, the king permitted Lord North to work a plan of reconciliation on the same day Parliament passed the New England Restraining Act, forbiding the New England colonies (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire) from trading with any nation other than Britain and its Caribbean colonies. It also barred the New Englanders from using the North Atlantic fishing grounds.84 The Act was later expanded to five additional American colonies.85

The Colonies Begin to Think and Feel Together, 1775

As Great Britain’s treatment of the colonies became more heavy-handed and intolerant, many Americans, including some of those loyal to Great Britain, agreed that Parliament and the King were acting unjustly. Some civic leaders argued that the colonies could do nothing about these unjust actions because they were too weak. When someone made this argument in the Virginia legislature, Patrick Henry rejected it and urged decisive action, telling the members:

Sir, we are not weak if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people armed in the holy cause of liberty and in such a country as that which we possess are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us. Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God Who presides over the destinies of nations, and Who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave….Gentlemen may cry, “Peace, Peace,” but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!86

Henry’s speech includes many Biblical ideas, quotations, and references, including from 2 Chronicles 32:8, Deuteronomy 32:4, 2 Thessalonians 1:6, Psalm 75:7, Daniel 4:17, Ecclesiastes 9:11, Jeremiah 6:14, 8:11, and Matthew 20:6. This affirms his familiarity with the Bible, and since he did not feel it necessary to identify the source of his quotes and ideas to the listeners, it also suggests he believed they were familiar with the Bible as well.

Henry knew that the time for words had passed and the time for united action had arrived, and his references to Scripture helped make the point in a clear and dramatic manner.

- Office of the Historian, “Treaty of Paris, 1763,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris) (accessed on March 1, 2017). See also George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, pp. 451-454 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=481).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, p. 452 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=482). See also “The Treaty of Paris (1763) and its Impact,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/8d.asp) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 163-168 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=179). See also “British Reforms and Colonial Resistance, 1763-1766,” Library of Congress (at: https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/amrev/britref/) (accesse on March 1, 2017). Read the original proclamation setting these boundaries from The London Gazette dated October 4 to October 8, 1763 (at: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/10354/page/1).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. II, pp. 42-48 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4w9h;view=1up;seq=60). See also “Navigation Acts,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Navigation-Acts) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 187-189 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=204). See also “1764 – Sugar Act,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/sugar-act/1764-april-5-sugar-act/).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, p. 186 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=202).

- See, for example, William Pope Hazard, The American Guide Book (Philadelphia: George S. Appleton, 1846), Part 1, p. 34 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=HFVKAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA34#v=onepage&q&f=false); “No Taxation Without Representation,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/headline/no-taxation-without-representation-2/) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles A. Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, From the Discovery of the Continent by Christopher Columbus to the Present Time (Hartford: J. Seymour Brown, 1842), pp. 213-214 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=3F49AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA213#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- Hampton L. Carson, The History of the Supreme Court of the United States (Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler, 1902), Vol. I, pp. 29-35 (at: https://books.google.com/books?

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 201 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=227). See also “Quartering Act,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Quartering-Act) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles Botta, History of the United States of America (London: A. Fullarton & Co., 1850), Vol. II, pp. 29-33 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=u9FSAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA29#v=onepage&q&f=false). See also “1765 – Stamp Act,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/stamp-act/1765-november-1-stamp-act/) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles A. Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, From the Discovery of the Continent by Christopher Columbus to the Present Time (Hartford: J. Seymour Brown, 1842), pp. 204-205 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=3F49AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA204#v=onepage&q&f=false). See also “Sons of the Liberty,” Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum (at: https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/sons-of-liberty) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 308-321 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=324). See also “The Stamp Act Riots,” History, August 14, 2015 (at: https://www.history.com/news/the-stamp-act-riots-250-years-ago).

- See, for example, George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 274-278 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=290); “New York Merchants Non-importation Agreement; October 31, 1765,” The Avalon Project (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/newyork_non_importation_1765.asp); “The Stamp Act Controversy,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/9b.asp) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 434-437, 445 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=450); “The Declatory Act, March 18, 1766,” Constitution Society (at: https://www.constitution.org/bcp/decl_act.htm).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 76-80 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=102). See also “The Townshend Acts,” Massachusetts Historical Society (at: https://www.masshist.org/revolution/townshend.php) (accessed on March 2, 2017); “Townshend Acts,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Townshend-Acts) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- “Writs of Assistance: 1761-72,” The Founders Constitution (at: https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendIVs2.html), quoting from Quincy’s Rep. (Mass.).

- Fore more information, see an “Editorial Note” in the online collection of Legal Papers of John Adams, Volume 2 (at: https://www.masshist.org/publications/apde2/view?id=ADMS-05-02-02-0006-0004-0001).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 136 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=162).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 76, 274 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=274).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 279-281 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=305). See also “The Virginia Resolves of 1769,” TeachingAmericanHistory.org (at: https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/the-virginia-resolves-of-1769/) (accessed on March 7, 2017); “Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, 17 May 1769,” National Archives (at: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0019).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 281 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=307).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 281-282 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=307).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 365 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=391)

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 350-354 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=376).

- “The Declaratory Act, March 18, 1766,” Documents of American History, ed. Henry Steele Commager (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), 60-61.

- Moses Coit Tyler, The Literary History of the American Revolution: 1763-1783 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897), 2:21.

- Samuel Adams, “The House of Representatives of Massachusetts to the Speakers of the Other Houses of Representatives,” The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 1.186.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), 6:163-165.

- Frederic Kidder, History of the Boston Massacre (NY: Joel Munsell, 1870), 29.

- John Quincy Adams & Charles Francis Adams, The Life of John Adams (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1874), 1:144-145.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), 10:203, to Dr. Jedediah Morse on January 5, 1816.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 416-418, 441 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=442). See also “Gaspee Virtual Archives” gaspee.org (at: https://www.gaspee.org/) (accessed on March 7, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 428, 444-445, 454-455 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=454).

- Alden Bradford, Memoir of the Life and Writings of Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, D.D. (Boston: C.C. Little & Co., 1838), 427-430, to James Otis, June 8, 1766.

- William V. Wells, The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865), 1:496-497.

- Richard Frothingham, Life and Times of Joseph Warren (Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1865), 212, James Warren to Samuel Adams on December 8, 1772.

- Warren-Adams Letters (The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917), 1:14, Samuel Adams to James Warren on December 9, 1772.

- Samuel Adams, The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906), 2:355, “The Rights of the Colonists, a List of Violations of Rights and a Letter of Correspondence,” November 20, 1772.

- The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1865), 3:379, “Last Will and Testament of Samuel Adams,” December 29, 1790.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), 5:194-195.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 457-459 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=483). See also “Significance of the Tea Act, 1773,” Boston Tea Party Historical Society (at: https://www.boston-tea-party.org/tea-act.html) (accessed on March 7, 2017).

- Claude Van Tyne, The Causes of the War of Independence (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922), 376-377. See also John Fiske, The American Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919, originally published 1891), 81.

- Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin (Philadelphia: William Duane, 1809), 6:310, to Thomas Cushing on June 4, 1773, in which Franklin said, “They have no idea that any people can act from any other principle but that of interest; and they believe that three pence on a pound of tea, of which one does not perhaps drink ten pounds in a year, is sufficient to overcome all the patriotism of an American.”

- John Fiske, The American Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919, originally published 1891), 81.

- Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 306; and George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1854), 6:485.

- The events leading up the Boston Tea Party are covered in Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 306-308; and George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1854), 6:482-487.

- Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 309.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1854), 6:488, 493, 525; and 7:142-143.

- “The Boston Port Act, March 31, 1774,” Documents of American History, ed. Henry Steele Commager (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), 71-72.

- For information about specific shipments that came into Boston from across the American colonies, see: George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1858), 7:73-75.

- Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 324.

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 1:105–107, “Resolution of the House of Burgesses Designating a Day of Fasting and Prayer, 24 May 1774.”

- Richard Frothingham, The Rise of the Republic of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1872), 324.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), 10:283, to Hezekiah Niles on February 13, 1818.

- “Massachusetts Government Act: May 20, 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/mga.html).

- “Quartering Act of 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/q74.html).

- “Quebec Act: June 22, 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/cqa.html); “The Intolerable Acts,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/9g.asp).

- From a reprint of a Proclamation of the Virginia House of Burgesses for a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer on the 1st Day of June, Tuesday, the 24th of May, 14 GEO. III 1774.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 52-53 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=64).

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- See, for example, an 1827 document from the American Bible Society signed by John Jay as President from WallBuilders’ Collection, accessed on May 25, 2020, wallbuilders.com/american-bible-society-certificate-signed-john-jay/; and letters from John Jay to Rev. Morse on January 1, 1813; to John Murray, Jr. on April 15, 1818; to Edward Livingston on July 28, 1822; to the Corporation of Trinity Church, undated; an “Address to the American Bible Society” on May 9, 1822; and more from The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry Johnston (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890-1893), 4 vols., passim.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:23-24, to Abigail Adams on September 16, 1774.

- Boston Gazette, September 26, 1774, containing an extract of a letter from Samuel Adams to Joseph Warren on September 9, 1774. See also Samuel Adams, “Samuel Adams to Joseph Warren, September 9, 1774,” Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, ed. Edmund C. Burnett (Washington DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1921), 1.26-27.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1850), 2:378, from his diary entry of September 10, 1774.

- Letters of Delegates to Congress, ed. Paul H. Smith (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1976), 1:45, from Samuel Ward’s diary for September 7, 1774.

- Silas Deane, The Silas Deane Papers (New York: New York Historical Society, 1886), 1:20, to Elizabeth Deane on September 7, 1774. See alsoLetters of Delegates to Congress, ed. Paul H. Smith (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1976), 1:34, Silas Deane to Elizabeth Deane on September 7, 1774.

- Silas Deane, The Silas Deane Papers (New York: New York Historical Society, 1886), 1:20, letter from September 7, 1774.

- Silas Deane, The Silas Deane Papers (New York: New York Historical Society, 1886), 1:20, to Elizabeth Deanne on September 7, 1774. See also Letters of Delegates to Congress, ed. Paul H. Smith (Washington DC: Library of Congress, 1976), 1:34, Silas Deane to Elizabeth Deane on September 7, 1774.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, ed. Charles Frances Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 2:368, diary entry for September 7, 1774.

- Daniel Webster, Mr. Webster’s Speech in Defence of the Christian Ministry and In favor of the Religious Instruction of the Young. Delivered in the Supreme Court of the United States, February 10, 1844, in the Case of Stephen Girard’s Will (Washington DC: Gales and Seaton, 1844), 47-48.

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:46, to Abigail Adams on June 17, 1775.

- Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington Printing Office, 1906), 2:87-88, “Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer,” for July 20, 1775; 4:208-209, “Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer,” for May 17, 1776; 6:1022, “Fasting and Humiliation,” December 11, 1776; 9:854-855, “Thanksgiving and Praise,” for December 18, 1777; 10:229-230, “Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” for April 22, 1778; 12:1139, “Thanksgiving and Praise,” for December 30, 1778; 13:343-344, “Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” for May, 1779; 15:1191-1193, “Thanksgiving,” for December 9, 1779; 16:252-253, “Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” for April 26, 1780; 18:950-951, “Thanksgiving and Prayer,” for December 7, 1780; 19:284-286, “Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer,” for May 3, 1781; 21:1074-1076, “Thanksgiving and Prayer,” for December 13, 1781; 22:137-138, “Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” for April, 1782; 23:647, “Thanksgiving,” for November 28, 1782; 25:699-701, “Thanksgiving,” for December, 1783.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 127-134 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=139). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 139-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=150). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 146-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=158).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 149-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=161). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 217-227 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=229).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, p. 239 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=251); The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the end of the Elventh Parliament of Great Britain (Cambridge: John Archdeacon, 1775), Vol. XXXI, pp. 4-11, “An act to restrain the trade and commerce of the provinces of Massachusett’s Bay and New Hampshire, and colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island and Providence Plantation in North America, to Great Britain, Ireland, and the British islands in the West Indies” (at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B09RAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA4=onepage&q&f=false)

- The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the end of the Elventh Parliament of Great Britain (Cambridge: John Archdeacon, 1775), Vol. XXXI, pp. 37-43, “An act to restrain the trade and commerce of the colonies of New Jersey, Philadelphia, Mayland, Virginia, and South Carolina, to Great Britain, Ireland, and the British islands in the West Indies, under certain conditions and limitations” (at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B09RAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA37=onepage&q&f=false).

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1818), 123, speech on March 23, 1775.