1.3 – Pastors Pave the Way for Independence 2.0

A Revolution of Hearts & Minds

John Adams, after he had served as both Vice-President and President, penned in 1818 that the Revolution had been won even before the first shot was fired.1 It was won in the minds and hearts of the people emboldened in the spirit of religious liberty that grew out of the Great Awakening that occurred in the colonies between 1730-1770. For four decades, itinerant preachers went throughout the colonies spreading the news of renewed belief in the sovereignty of God and commitment to Biblical living and faith in Jesus Christ, and thousands responded with great enthusiasm. George Whitefield, the most widely traveled and best known of these preachers, had tremendous influence along with Jonathan Edwards, John and Charles Wesley, Samuel Davies, and Charles Chauncy.2

George Whitefield and the First Great Awakening

Many early colonists were sincerely pious and devout, especially in the northern colonies, but each generation must decide for itself whether to obey and follow God’s Word. It is a sad truth of both history and human nature that just because something begins in a good manner does not mean it will remain that way, and by the time Georgia was founded in the 1730s (well over a century after the first colonies), America was experiencing a definite lull in genuine Biblical practice.

The Rev. Jonathan Edwards affirmed that Massachusetts was in a “degenerate time” with “dullness of religion.”3 And in Pennsylvania, the Rev. Samuel Blair (who later became a chaplain of Congress) likewise acknowledged that “religion lay, as it were, dying and ready to expire its last breath of life in this part of the visible church.”4 In only a few short generations, the excitement and enthusiasm of a vibrant Christian life had departed from many Americans and their churches.

A spiritual reset was needed—and it happened. Known as the First Great Awakening, a series of revivals swept America from the 1730s through the 1760s, in part because of the hard work and leadership of many notable ministers, including Jonathan Edwards (a Congregationalist) as well as William Tennant and Samuel Davies (both Presbyterians), who helped set the colonies aflame spiritually.

A 1739 newspaper reported a typical local schedule for Whitefield:

On Friday last, the Rev. Mr. Whitefield arrived here [Philadelphia] with his friends from New York, where he preached eight times; and on his return hither, preached at Elizabethtown [New Jersey], Brunswick, Maidenhead, Trenton, Neshaminy, and Abingdon. He has preached twice every day in the church to great crowds, except Tuesday, when he preached at Germantown [Pennsylvania], from a balcony to about 5,000 people in the street; and last night the crowd was so great to hear his farewell sermon [on leaving Philadelphia], that the church could not contain one half, whereupon they withdrew to Society Hill, where he preached from a balcony to a multitude computed at not less than 10,000 people. He left this city today, and is to preach at Chester, tomorrow at Willings Town, Saturday at New Castle, Sunday at White Clay Creek, and so proceed on his way to Georgia, through Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina.7

A week later, the paper gave a follow up on the meetings it had mentioned:

[T]he Rev. Mr. Whitefield…preached there [in Chester] to about 7,000; on Friday he preached at Willings Town to about 5,000; on Saturday at New Castle, and the same evening at Christian Bridge; on Sunday at White Clay Creek he preached twice, resting about half an hour between the sermons, to about 8,000 people, of whom about 3,000 it’s computed came on horseback; and though it rained most of the time, yet they patiently stood in the open air. He then proceeded on his journey, preaching to multitudes wherever he went.8

Whitefield maintained a grueling travel and speaking schedule in countless locations across the nation. Additionally, many other local ministers were also active in their state and regions throughout that time of awakening.

As a result, thousands were converted, and churches were filled. Today this movement is often characterized as a national revival, but to be more accurate it was really thousands of local revivals in so many different communities across America that eventually the entire nation was changed—that is, the revival grew from families and towns outward to the nation, not from the nation inward to towns and families.

During this time, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin developed a close friendship with the Rev. George Whitefield. Franklin appreciated the positive impact the revival had in his hometown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, reporting:

It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world were growing religious so [that] one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.9

The Rev. Jonathan Edwards similarly saw positive effects in his community of Northampton, Massachusetts, reporting:

There has been vastly more religion kept up in the town (among all sorts of persons) in religious exercises and in common conversation—there has been a great alteration among the youth of the town with respect to revelry, frolicking, profane and licentious conversation, and lewd songs—and there has also been a great alteration amongst both old and young with regard to tavern-hunting….There has also been an evident alteration with respect to a charitable spirit to the poor.10

Godliness swept the colonies and a love for the Bible and its teachings was renewed among citizens and families in local communities across the nation.

Whitefield had a substantial impact on America by changing the lives and thinking of countless Americans. It is estimated that the total number of those who attended his meetings was over 10 million,11 and hundreds of thousands were transformed by his message. (Since America had only 3 million inhabitants at the time,12 not only did most Americans hear Whitefield preach but many likely heard him several times.)

“Father Abraham” Sermon

Clearly, George Whitefield substantially impacted America by transforming thousands of lives, including that of John Marrant (and also those John subsequently reached). But Whitefield also had a significant influence in preparing Americans for the approaching War for Independence, especially by helping break down the rigid barriers that separated the colonies from one another.

Those early colonies were not like today’s states within the United States. At that time, they behaved much more like the separate nations of Europe: many did not like the others, and each was largely independent, having its own currency, and separate militias. They even had armed conflict among themselves over borders, such as the eight years of skirmishes between Pennsylvania and Maryland that became known as Cresap’s War (1730-1738). There were similar conflicts between New York and her neighbors, as well as with Virginia and hers.

Another point of vigorous dispute between the colonies was over religion. All were Christian, but Pennsylvania tended to be predominantly Quaker; Virginia and South Carolina, Anglican; Massachusetts and Connecticut, Congregational; New York, Dutch Reformed; and so forth. Some of these Christian denominations were aggressively hostile toward the others—as in Virginia, where Anglicans would imprison, fine, and punish Quaker, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Christians who preached in their colony without approval from the State.13 Sadly, the American colonies had slowly begun to adopt some of the same deplorable aspects of Europe’s religious tyranny from which so many had earlier fled.

It was in this atmosphere of colonial disputes that Whitefield ministered. What message could he share that would be acceptable from one colony to the next?—what could he do to break down the walls that separated them?—how could he help them see they had more in common than different?

An answer was found in Whitefield’s “Father Abraham” sermon. It was heard by many Founding Fathers, and its unifying message challenged their thinking, remaining in their minds across the years. John Adams recounted this particular sermon to his friend Thomas Jefferson, describing how Whitefield pretended to be at the gates of Heaven talking with Abraham:

He [Whitefield] began: “Father Abraham,” with his hands and eyes gracefully directed to the heavens (as I have more than once seen him): “Father Abraham, whom have you there with you? Have you Catholics?” “No.” “Have you Protestants?” “No.” “Have you Churchmen?” [Anglicans]. “No.” “Have you Dissenters?” [Congregationalists]. “No.” “Have you Presbyterians?” “No.” “Quakers?” “No.” “Anabaptists?” [Amish and Mennonites]. “No.” “Whom have you there? Are you alone?” “No.” “My brethren, you have the answer to all these questions in the words of my next text: ‘He who feareth God and worketh righteousness, shall be accepted of Him’ [Acts 10:35].”14

In another account of that sermon recorded by an early historian, Whitefield closed by urging, “God help us all to forget party names and to become Christians in deed and in truth.”15

Whitefield’s theme was unity—that despite the many different denominations and points of strong doctrinal disagreement between them, there nevertheless was the crucially-important fact that they were all Christians. Whitefield preached this sermon many times throughout the colonies, and years after his death, the Founding Fathers found themselves in a situation that allowed them to put its message to practical use—but more on that later.

Whitefield’s contributions in laying the foundation for American independence were substantial, and many other ministers also exerted significant influence.

Other Ministers in the Great Awakening

Samuel Davies

Much of Davies’ adult life was spent in Virginia, where he preached across the state, organizing numerous churches. One of his famous sermons was for a military deployment in 1755. In it, he called the nation’s attention to a very young Colonel George Washington. He pointed out the miraculous Divine intervention that had just saved Washington’s life during Gen. Edward Braddock’s devastating defeat in Pennsylvania when Washington was serving with the British during the French and Indian War.18 Davies’ remarkable sermon, with its reference to a largely unknown George Washington, was published both in America and England, drawing attention to the young man.19

The influence of Davies on America was far reaching, including through the many lives he impacted. Consider, for example, his influence on Patrick Henry.

When Patrick was a young boy, his mother joined the church Davies pastored. She always took Patrick to church with her, and each Sunday as they rode home in their buggy, Mrs. Henry and Patrick would review the sermon. Hearing the great Davies preach week after week greatly influenced the development of Henry’s own oratorical skills. As affirmed by an early biographer, Henry’s “early example of eloquence…was Mr. Davies, and the effect of his teaching upon [Henry’s]after life may be plainly traced.”20

Henry went on to become not only one of the best-known figures of the American War for Independence but certainly one of its greatest orators, being known as the “The Voice of the Revolution” and the “Orator of Liberty.” And it was a minister of the Gospel who helped him become perhaps the most effective public speaker among the Founding Fathers.

While Henry openly acknowledged that Davies was “the greatest orator he ever heard,”21 Thomas Jefferson similarly called Henry “the greatest orator that ever lived.”22 Henry clearly had learned from the best!

Elisha Williams

The Congregationalist minister Elisha Williams (1694-1755) was a schoolteacher, Connecticut state representative, judge, and president of Yale. Also greatly influenced by the Rev. George Whitefield, he was not only a chaplain of New England’s military forces during the French and Indian War but also became a colonel and led troops in the field. In 1744, he wrote The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, which set forth Biblical principles of equality, liberty, and property. The ideas he preached were influential in shaping thinking leading up to the War for Independence.

Jonathan Mayhew, “Father of Civil Liberty”

In 1765, the British passed The Stamp Act, which levied improper taxes on the colonists. Resistance in the colonies to that measure was widespread and organized, and Benjamin Franklin was sent to the royal court in England to argue against the measure.26 Under unified pressure from civil and religious leaders, the following year the Stamp Act was repealed.

Mayhew, having witnessed the power of that unified stand, wrote to James Otis (mentor of Sam Adams, John Hancock, and other leading patriots), telling him: “You have heard of communion [i.e., unity] of the churches….[W]hile I was thinking of this,…[the] importance of a communion [unity] of the colonies appeared to me in a strong light.”27 Mayhew then proposed “to send circulars to all the rest” of the colonies28 to help achieve unity among them in both thinking and action on key issues. Mayhew’s suggestion later became reality through what became known as the Committees of Correspondence, which distributed both educational materials and breaking news among the colonies.

Mayhew’s impact was substantial in other areas as well. John Adams affirmed he was one of the individuals “most conspicuous, the most ardent, and influential” in the “awakening and revival of American principles and feelings” that led to our independence.29

So although few pastors had the reach and influence of Whitefield, there were scores of others who, like Davies, Williams, and Mayhew, impacted their communities by shaping the people and their thinking.

“Great Awakening” Sermons

Sermons preached and printed during the First Great Awakening helped produce Biblical thinking on numerous issues, including civil liberties, the necessity of resisting tyrannical rulers, limited government, equal rights, the evils of slavery, and much else. Sermon titles from that period affirm that Biblical truth was shown to be relevant to all areas of life. A few of the many sermons addressing political topics included:

- Civil Magistrates Must Be Just, Ruling in the Fear of God (1747), by Charles Chauncey30

- Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers (1750), by Jonathan Mayhew31

- Religion and Patriotism, the Constituents of a Good Soldier (1755), by Samuel Davies32

- The Advice of Joab to the Host of Israel Going Forth to War (1759), by Thaddeus MacCarty33

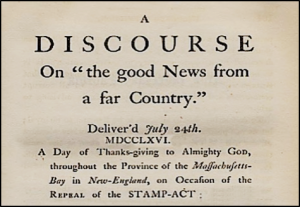

- Good News from a Far Country (1766), by Charles Chauncey34 (a sermon on the repeal of the Stamp Act)

- An Oration upon the Beauties of Liberty (1773), by John Allen35

- Scriptural Instructions to Civil Rulers (1774), by Samuel Sherwood36

- Jesus Christ the True King (1778), by Peter Powers37 (This sermon during the War for Independence resulted in the political cry “No King but King Jesus!”38)

These sermon titles illustrate that early pastors openly taught Biblical principles related to government and culture. As historian Alice Baldwin documented, such sermons were indispensable in shaping America’s unique view of civil and religious liberty:

There is not a right asserted in the Declaration of Independence which had not been discussed by the New England clergy before 1763.39

She further noted, “The Constitutional Convention and the written Constitution were the children of the pulpit.”40 No wonder Founding Father John Adams openly rejoiced that the “pulpits have thundered,”41 affirming that:

The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence were….the general principles of Christianity….I will avow that I then believed, and now believe, that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God; and that those principles of liberty are as unalterable as human nature.42

The First Great Awakening was foundational in preparing Americans in the Biblical character and worldview necessary for a lasting independence. It also molded the young men who became our Founding Fathers, and a number of them became ministers, also serving as political leaders.

The key to understanding how the Great Awakening impacted the independence movement, is to see how an individual’s change of heart toward God changed their relationship toward one another.

You literally had colonies fighting each other. In Virginia, Christians were killed for not adhering to the established religion. The years leading up to the American Revolution would not have made anyone think that unity was a possibility for the divided colonies. The division between Christian denominations was hard and sharp. God used preachers like John Whitefield during this time to help Americans begin to come together as Christians.

John Adams credited Whitefield’s influential sermon with creating a sense of brotherhood and unity among the previously divided colonies.

This revival gave American colonists a new awareness of their accountability to the God of the Bible, not only in their private lives but also their public activities as well. They rediscovered the same universal truth that had motivated the first Pilgrims: that all people, including kings and magistrates at all levels, are equally accountable to God. There is no divine right for officials at any level to arbitrarily rule over the people.43

If we look back to the earliest days of the Pilgrim settlements in the New World, we see how churches, literacy and education set the table for the First Great Awakening. Education of the young was a key part of community life.

As early as 1642, the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony was passing education legislation. The so-called “School Law” made it clear that education was a necessary part of a society’s success. It required the teaching of reading, writing, and also required that parents “catechize their children and servants in the grounds & principles of Religion.”

Five years later, the “Old Deluder Satan Law” was passed which said in part, “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures…It is therefore ordered that every township in this jurisdiction, after the Lord hath increased them to fifty households shall forthwith appoint one within their town to teach all such children as shall resort to him to write and read…” (see Four Centuries of American Education for more on the Massachusetts school laws)

As new settlements occurred, they were required to establish churches and schools. The stated goal of the school was to teach the next generation to read and study the Bible.44 At the time of the War of Independence, almost 85% of the people were literate, at least to the extent of being able to read their Bibles and a newspaper.45 Twelve of the thirteen colonial colleges founded before the War were instituted to train men for the pulpit ministry.46 Even College graduates who chose the law as a profession were trained equally in theology, since understanding the Bible was considered the beginning point for understanding the law.

The ideas of the Great Awakening spread throughout the colonies in large part through the wide distribution of printed sermons. Ben Franklin enthusiastically printed several of George Whitfield’s sermons.47 Even in small frontier settlements, we find groups gathering together in homes to read some of these great sermons. Whitefield could easily be considered one of America’s Founding Fathers considering the fact that he protested the Stamp Act48 and was one of the earliest advocates for American independence.49

Though not the only factor, in a very real way the Great Awakening served as a spark to the cause of independence. Even though they may have used different modes of worship, people in all parts of the colonies came to understand that they shared the same Judeo-Christian foundation. This rising sense of a shared destiny, founded on Biblical principles, helped lead them out of their colonial isolationist perspective. They began to see the common goal of independence as vital and necessary when the political storms broke out throughout the colonies.

Let us not forget the importance of a remnant in great movements throughout history. God has often used small, seemingly insignificant numbers of people to accomplish great things. Noah and his family, Gideon and his three-hundred, and the remnant that returned to rebuild Jerusalem with Nehemiah are all examples of how God is not limited by small numbers of people. Though estimates vary, when studying the times of the War for American Independence, it is estimated that when the conflict broke out there were approximately 2.5 million people living in the American colonies. Of those 2.5 million, estimates say that only about thirty-five percent favored independence, while another twenty-five percent favored loyalty to the King of England. The approximately 40 percent in the middle were mostly apathetic toward independence, and preferred to simply be left alone.50 Though small in numbers, God used the remnant of patriots in America to bring about a change that has shaped the modern world and brought freedom to countless millions.

Liberty or Death!

Patrick Henry

Many American leaders spoke out against the unjust Stamp Act, including ministers such as the Rev. George Whitefield and the Rev. Charles Chauncy and political leaders like James Otis, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry.

Patrick Henry was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses (the state legislature) shortly after the Stamp Act tax had been imposed.51 He was new in the state assembly, but when he found none of the senior legislative members willing to publicly oppose the tax, he felt compelled to take action. He therefore penned resolutions against the Stamp Act and introduced them in the legislature. Because several members were staunchly pro-British and supported whatever the British did, Henry reported, “Upon offering them [the resolutions] to the house, violent debates ensued. Many threats were uttered, and much abuse cast on me.”52

Henry reported that his speech had a significant impact in rallying the patriots in the Virginia legislature:

His passionate speech turned the tide. One early historian reported that Henry “was hailed as the leader raised up by Providence for the occasion,”55 and further explained:

America was filled with Mr. Henry’s fame, and he was recognized on both sides of the Atlantic as the man who rang the alarm bell which had aroused the continent. His wonderful powers of oratory engaged the attention and excited the admiration of men, and the more so as they were not considered the result of laborious training but as the direct gift of Heaven.56

Because of Henry’s efforts in conjunction with those of patriots in other states, the British Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. When unofficial word of that decision reached America, many pastors began preaching sermons in celebration.58 Then, when official word finally arrived, the Massachusetts legislature called a statewide day of prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God.59 On that day, the Rev. Charles Chauncy (a Massachusetts pastor who had openly opposed the Stamp Act) delivered a famous sermon commemorating the glorious event,60 as did many other ministers.61 Fifty years later, John Adams looked back and identified both Chauncy and that sermon as a catalyst in the early movement leading to independence.62

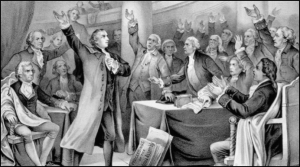

The next stop in our time machine finds us just outside St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, in March 1775, just one month before the confrontation at Lexington, Massachusetts. Inside the church, the Virginia House of Burgesses is meeting.63 Patrick Henry, known for his firebrand speeches, is awakening the Virginia House of Burgesses to the rising tensions in Massachusetts, and challenging them to a call to arms.

“If we wish to be free . . . we must fight! An appeal to arms and the God of Hosts is all that is left us! They tell us we are weak . . . shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? . . . Sir, we are not weak . . . Three million people armed in the holy cause of liberty and in such a country . . . are invincible to any force that our enemy can send against us. Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations; and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave . . . Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”64

Discover the convergence of Biblical teaching and love of one’s country as you watch the following episode of Chasing American Legends. You will visit two Founding Era churches and learn how their pastors played a critical role in American Independence.

As news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord spread, colonials were beginning to see that these events required action. On May 31, 1775, a provincial convention in Mecklenburg County, NC, passed their own resolutions setting forth the proper relationship between a government and the people.65 Note especially the wording of the second resolution as compared with the Declaration of Independence of 1776.

The Mecklenburg Resolutions

I. Resolved: That whosoever directly or indirectly abets, or in any way, form, or manner countenances the unchartered and dangerous invasion of our rights, as claimed by Great Britain, is an enemy to this country — to America — and to the inherent and inalienable rights of man.

II. Resolved: That we do hereby declare ourselves a free and independent people; are, and of right ought to be a sovereign and self-governing association, under the control of no power, other than that of our God and the General Government of the Congress: To the maintenance of which Independence we solemnly pledge to each other our mutual co-operation, our Lives, our Fortunes, and our most Sacred Honor.

III. Resolved: That as we acknowledge the existence and control of no law or legal officer, civil or military, within this county, we do hereby ordain and adopt as a rule of life, all, each, and every one of our former laws, wherein, nevertheless, the Crown of Great Britain never can be considered as holding rights, privileges, or authorities therein.

IV. Resolved: That all, each, and every Military Officer in this country is hereby reinstated in his former command and authority, he acting to their regulations, and that every Member present of this Delegation, shall henceforth be a Civil Officer, viz: a Justice of the Peace, in the character of a Committee Man, to issue process, hear and determine all matters of controversy, according to said adopted laws, and to preserve Peace, Union, and Harmony in said county, to use every exertion to spread the Love of Country and Fire of Freedom throughout America, until a more general and organized government be established in this Province.

Olive Branch Rejected

As we continue the journey toward independence, let’s check in on the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia, where they have elected John Hancock to be President of the assembly.66 Though still a year away from declaring independence, armed conflict has begun. The Congress appoints George Washington commander of the Continental Army.67 In that same month of June, a major battle is fought just north of Boston, on Bunker’s Hill and Breed’s Hill. While the British technically won the battles after the Americans ran out of ammunition, the British sustained heavy casualties.68

Even after the military engagements of 1775, our Congress still sent an Olive Branch Petition (so called because the olive branch is a symbol of peace) to the king, professing their ties to the crown and hoping for a restoration of relationship.69 This would be America’s final attempt at a resolution after eleven years of British encroachments on American freedom. The king and his government spurned the petition without even reading it and decreed even greater restrictions on the colonies.70

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1856), Vol. X, pp. 282-289, to H. Niles on February 13, 1818 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=fWt3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA282#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- See resources on the First Great Awakening. For example, Joseph Tracy, The Great Awakening. A History of the Revival of Religion in the Time of Edwards and Whitefield (Boston: Charles Tappan, 1845).

- Jonathan Edwards, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (Edinburgh: Thomas Lumisden and John Robertson, 1738), 16

- Joseph Tracy, The Great Awakening: A History of the Revival of Religion in the Time of Edwards and Whitefield (Boston: Charles Tappan, 1845), 26, by the Rev. Samuel Blair on August 6, 1744.

- Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography, eds. James Grant Wilson and John Fiske (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1889), 6:478, s.v. “Whitefield, George.”

- See, for example, “George Whitefield: Did You Know?” Christian History (April 1993), accessed on May 25, 2020, www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-38/george-whitefield-did-you-know.html; and Dave Schleck, “CW to Recreate Visit of Famous Preacher,” Daily Press (December 16, 1995), accessed on May 25, 2020, www.dailypress.com/news/dp-xpm-19951216-1995-12-16-9512160076-story.html.

- Williamsburg Virginia Gazette (January 17, 1740), 3, entry dated November 29, 1739.

- Williamsburg Virginia Gazette (January 17, 1740), 3, entry dated December 6, 1739.

- Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, ed. John Bigelow (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Company, 1868), 253.

- Jonathan Edwards, The Works of President Edwards, eds. Edward Williams and Eward Parsons (New York: G. & C. & H. Carvill, 1830), 1:160, to a Boston minister on December 12, 1743.

- Chambers’s Encyclopedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge, eds. William & Robert Chambers (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1901), 10:642, s.v. “Whitefield, George.”

- See the numbers given by Patrick Henry in Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry, William Wirt (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1818), 123, speech on March 23, 1775; the same number is given by John Adams in his address “To the Inhabitants of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay, 6 February 1775,” The John Adams Papers, ed. Robert J. Taylor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977), 2:246.

- See, for example, James Madison, The Writings of James Madison, ed. Galliard Hunt (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), 21, to William Bradford Jr. on January 24, 1774; Robert Semple, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Baptists in Virginia (Richmond: Robert Semple, 1810), 14, 29-30; A Companion to Thomas Jefferson, ed. Francis Cogliano (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 78; Cyclopedia of Methodism, ed. Matthew Simpson (Philadelphia: Everts & Stewart, 1878), 890.

- Thomas Jefferson The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb (Washington DC: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), 14:19-20, from John Adams on December 3, 1813.

- Memoirs of the Life and Character of the Rev. George Whitefield (Lexington: Thomas P. Skillman, 1823), 308.

- William Edward Schenck, An Historical Account of the First Presbyterian Church of Princeton, N.J.: Being a Sermon Preached on Thanksgiving Day, December 12, 1850 (Princeton: John T. Robinson, 1850), 23; Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), 5:102, s.v. “Davies, Samuel.”

- Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), 5:102, s.v. “Davies, Samuel.”

- Samuel Davies, Religion and Patriotism, the Constituents of a Good Soldier. A Sermon Preached to Captain Overton’s Independent Company of Volunteers, Raised in Hanover County, Virginia, August 17, 1755 (Philadelphia, 1756), 10n [Evans #7403]: “As a remarkable instance of this, I may point out to the public that heroic youth, Col. Washington, whom I cannot but hope Providence has hitherto preserved in so signal a manner for some important service to his country.”

- For more on this extraordinary historical incident, see The Bulletproof George Washington at shop.wallbuilders.com.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry, Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891), 1:16.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry, Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891), 1:15.

- Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography, eds. James Grant Wilson and John Fiske (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1889), 3:175, s.v. “Henry, Patrick.”

- Jonathan Mayhew, A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-resistance to the Higher Powers (Boston: D. Fowle, 1750) [Evans #6549].

- John Adams, Letters of John Adams, Addressed to His Wife, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), 1:152, to Abigail Adams on August 14, 1776.

- Henry S. Randall, The Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858), 3:383, 487.

- Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Jared Sparks (London: Benjamin Franklin Stevens, 1882), 312, letter from Joseph Galloway to William Franklin on April 29, 1766.

- Alden Bradford, Memoir of the Life and Writings of Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, D.D. (Boston: C.C. Little & Co, 1838), 429, from Jonathan Mayhew to James Otis on June 8, 1766.

- Alden Bradford, Memoir of the Life and Writings of Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, D.D. (Boston: C.C. Little & Co, 1838), 428, from Jonathan Mayhew to James Otis on June 8, 1766.

- John Adams, Novanglus and Massachusettensis: or Political Essays Published in the year 1774 and 1775 (Boston: Hews & Goss, 1819), 235 [Shaw #46923].

- Charles Chauncy, Civil Magistrates Must Be Just, Ruling in the Fear of God. A Sermon Preached Before his Excellency, William Shirley, the Honorable His Majesty’s Council, and House of Representatives, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, May 27, 1747 (Boston: Printed by Order of the Honorable House of Representatives, 1747) [Evans #5919].

- Jonathan Mayhew, A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers (Boston: D. Fowle, 1750) [Evans # 6549].

- Samuel Davies, Religion and Patriotism, the Constituents of a Good Soldier. A Sermon Preached to Captain Overton’s Independent Company of Volunteers, Raised in Hanover County, Virginia, August 17, 1755 (Philadelphia, 1756) [Evans #7403].

- Thaddeus MacCarty, The Advice of Joab to the Host of Israel Going Forth to War, Considered and Urged. In Two Discourses Delivered in Worchester, April 5, 1759. Being the Day of the Public Annual Fast (Boston: Thomas and John Fleet, 1759) [Evans #8388].

- Charles Chauncy, A Discourse on “the Good News from a Far Country.” Delivered July 24th. A Day of Thanksgiving to Almighty God, throughout the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New England, on Occasion of the Repeal off the Stamp Act (Boston: Kneeland and Adams, 1766) [Evans #10255].

- John Allen, An Oration upon the Beauties of Liberty, or The Essential Rights of the Americans, Delivered at the Second Baptist Church in Boston. Upon the Last Annual Thanksgiving (Wilmington: James Adams, 1773) [Evans #14457].

- Samuel Sherwood, A Sermon Containing Scriptural Instructions to Civil Rulers and all Freeborn Subjects: In which the Principles of Sound Policy and Good Government are Established and Vindicated, and Some Doctrines Advanced and Zealously Propagated by New England Tories are Considered and Refuted. Delivered on the Public Fast, August 31, 1774 (New Haven: TNS Green, 1774) [Evans #13614].

- Peter Powers, Jesus Christ the True King and Head of Government. A Sermon Preached Before the General Assembly of the State of Vermont, on the Day of Their First Election, March 12, 1778, at Windsor (Newburyport: John Mycall, 1778) [Evans #16019].

- This quote is a summary of a statement found in the records of Parliament in April 1774: “If you ask an American, ‘Who is his master?’ He will tell you he has none—nor any governor but Jesus Christ.” Hezekiah Niles, Principles and Acts of the Revolution in America (Baltimore: William Ogden Niles, 1822), 198.

- Alice M. Baldwin, The New England Clergy and the American Revolution (Durham: Duke University Press, 1928), 170.

- Alice M. Baldwin, The New England Clergy and the American Revolution (Durham: Duke University Press, 1928), 134.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 2:154, diary entry for December 18, 1765.

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1856), 10:45-46, to Thomas Jefferson on June 28, 1813.

- See, for example, sermons on topics such as: the repeal of the Stamp Act (at: https://wallbuilders.com/sermon-stamp-act-repeal-1766/); election sermons such as this one from 1769 (at: https://wallbuilders.com/sermon-election-1769-massachusetts/); a good soldier (at: https://wallbuilders.com/sermon-military-1755/).

- The Code of 1650 (Hartford: Silas Andrus, 1822), pp. 92-94 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=i3ljAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- Jack Lynch, ” ‘Every Man Able to Read’ Literacy in Early America,” Colonial Williamsburg, Winter 2011 (at: https://www.history.org/foundation/journal/Winter11_newformat/literacy.cfm)

- See more about the founding of early American colleges in Notes on College Charters (Providence: Brown University, 1910) (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=o_ZBAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false); Thomas Clap, President of Yale College, Religious Constitutions of Colleges, Especially of Yale-College in New Haven in the Colony of Connecticut (New-London: T. Green, 1754), pp. 1,4 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=wNUCAAAAQAAJ&pg=PP7#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- A November 15, 1739 notice by Franklin in The Pennsylvania Gazette mentions his intention to publish “journals and sermons” given to him by Whitefield. See: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0052.

- Stephen Mansfield, Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield (Cumberland House, 2001), p. 112.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1858), Vol. V, p. 193.

- Calhoon, “Loyalism and neutrality” in Greene and Pole, A Companion to the American Revolution (2000) p. 235. The population of America in 1770 was just over 2.1 million, see “Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics,” Census Bureau, table on p. 1168 (at: https://www2.census.gov/prod2/statcomp/documents/CT1970p2-13.pdf).

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 51.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 58, handwritten note by Patrick Henry on the back of the 1765 resolutions he presented relating to the Stamp Act.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 65.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 58, handwritten note by Patrick Henry on the back of the 1765 resolutions he presented relating to the Stamp Act.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry, Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891), 1:94.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry, Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891), 1:101.

- Thomas Jefferson, Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1914), 8.

- See, for example, Samuel Stillman, Good News from a Far Country, A Sermon Preached at Boston, May 17, 1766, upon the Arrival of the Important News of the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Boston: Kneeland & Adams, 1766) [Evans #10503]; Nathaniel Appleton, A Thanksgiving Sermon on the Total Repeal of the Stamp-Act, Preached in Cambridge New-England, May 20th, in the Afternoon preceding the Public Rejoicings of the Evening upon that Great Occasion (Boston: Edes and Gill, 1766) [Evans #10230]; Jonathan Mayhew, The Snare Broken, A Thanksgiving-Discourse, Preached at the Desire of the West Church in Boston, N.E., Friday May 23, 1766, Occasioned by the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Boston: R. & S. Draper, 1766) [Evans #10389]; Elisha Fish, Joy and Gladness: A Thanksgiving Discourse, Preached in Upton, Wednesday, May 28, 1766; Occasioned by the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Providence: Sarah Goddard and Co., 1767) [Evans #10612]; David Sherman Rowland, Divine Providence Illustrated and Improved, A Thanksgiving Discourse, Preached (By Desire) in the Presbyterian, or Congregational Church in Providence, N.E., Wednesday June 4, 1766, Being His Majesty’s Birth Day, and Day of Rejoicing, occasioned by the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Providence: Sarah Goddard and Co., n.d.) [Evans #10483]; John Joachim Zubly, The Stamp-Act Repealed, A Sermon, Preached in the Meeting at Savannah in Georgia, June 25th, 1766 (Savannah, 1766) [Evans #10531]; Benjamin Troop, A Thanksgiving Sermon, upon the Occasion of the Glorious News of the Repeal of the Stamp Act; Preached in New-Concord, in Norwich, June 26, 1766 (New London: T. Green, 1766) [Evans #10506].

- Francis Bernard, “A Proclamation for a Day of Public Thanksgiving,” issued on July 4, 1766, to be observed on July 24, 1766 [Evans #10380].

- Charles Chauncy, A Discourse on “The Good News from a Far Country.” Delivered July 24th. A Day of Thanksgiving to Almighty God, throughout the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New-England, on Occasion of the Repeal of the Stamp Act (Boston: Kneeland and Adams, 1766), accessed on May 25, 2020, wallbuilders.com/sermon-stamp-act-repeal-1766/ [Evans #10255].

- See, for example, Joseph Emerson, Thanksgiving Sermon Preach’d at Pepperrell, July 24th 1766, A Day Set Apart by Public Authority as a Day of Thanksgiving on the Account of the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Boston: Edes and Gill, 1766) [Evans #10293]; William Patten, A Discourse Delivered at Hallifax in the County of Plymouth, July 24th 1766, on the Day of Thanksgiving to Almighty God, throughout the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New England, for the Repeal of the Stamp-Act (Boston: D. Kneeland, 1766) [Evans #10440].

- John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1856), 10:191, to Dr. Jedediah Morse on December 5, 1815.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, p. 272 (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=284).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 273-274 (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=285).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 370-373 (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=382).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 353, 378 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=365). For more general information on the Second Continental Congress, see: https://www.ushistory.org/us/10e.asp; https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 389-390, 393 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=401). See also U.S. Army Center of Military History, “Washington takes command of Continental Army in 1775,” U.S. Army, June 5, 2014 (at: https://www.army.mil/article/40819).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 416-435 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=428).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1860), Vol. VIII, pp. 37-38 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtki;view=1up;seq=41); Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Government Printing Offce, 1905), Vol. II, pp. 158-162, July 8, 1775 (at: https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=002/lljc002.db&recNum=157&itemLink=D?hlaw:8).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1860), Vol. VIII, pp. 130-134 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtki;view=1up;seq=134).