1.2 – Who Shot First? 2.0

The Shot Heard ‘Round The World

The Battle of Lexington, 1775

The Rev. Clark had been teaching the Biblical principles of liberty to his church members and had prepared them to defend themselves if necessary. After being informed that British troops were on their way to Lexington, Clark was asked if the people would fight. He responded that he had trained them for that very hour.3

The “shot heard around the world” (that is, the first shot in the first battle of the American War for Independence) took place the next morning, April 19, 1775. Approximately 70 members of the Rev. Clark’s congregation,4 including both black and white parishioners, gathered on the lawn of the church to face what Clark counted to be 800 British.5 At the end of the skirmish, 18 Americans—including white patriot John Robbins and black patriot Prince Estabrook—had been killed or wounded. All 18 of these brave Americans were members of Rev. Clark’s church.6 After watching that momentous scene, the Rev. Clark declared, “From this day will be dated the liberty of the world!”7

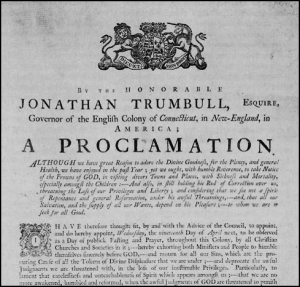

a day of public fasting and prayer…that God would graciously pour out His Holy Spirit on us, to bring us to a thorough repentance and effectual reformation…That He would restore, preserve, and secure the liberties of this and all the other American colonies, and make this land a mountain of holiness and habitation of righteousness forever.8

The American Minutemen, who faced an overwhelmingly larger British force that day, had been instructed not to fire at the British unless the British first shot at them. Captain John Parker, a member of the Rev. Clark’s church, specifically told them “Don’t fire unless fired upon!”10

After the battle, British General Thomas Gage, who was not at the conflict, claimed that the Americans had fired the first shot, but Pastor Clark, who had been an eyewitness, emphatically responded, “nothing can be more certain than the contrary, and nothing more false, weak, or wicked than such a representation.”11 He continued, “A cloud of witnesses [Hebrews 12:1], whose veracity [truthfulness] cannot be justly disputed, upon oath have declared in the most express and positive terms ‘that the British troops fired first’.”12 The question of who fired first might seem to be of little consequence today, but not to those patriots. They believed that to be under the blessing of God was crucial; and this would not occur if they began the fight, but only if they responded in self-defense.

The Rev. Clark was committed to presenting a Biblical view of issues to his parishioners, including on war and self-defense. For years he had taught, like many others in his day, that God would not bless an offensive war but only a defensive one.13 Thus, if an individual, city, community, colony, or nation was attacked, it had a God-given right to defend itself and could engage in war to protect the people, their property, and their rights; but it could not start the fight.14 This is why Captain Parker had issued his order.

The Battle of Lexington was followed later that same day by the Battle of North Bridge at Concord, where 400 Americans again engaged the British15. Toward the end of the day came the extended battle along the road to Boston as the British troops withdrew from Concord and attempted to reach safety. In their panicked retreat, they wantonly shot Americans and tried to kill wounded Americans in violation of the rules of warfare. They also burned American homes and farms.16 A rapidly growing number of colonists responded to fight back against the British rampage, often firing at the British from behind trees and stone walls at different places along both sides of the road.

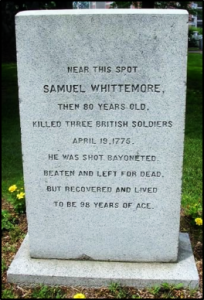

Samuel Whittemore

Elderly Samuel took up a location by himself behind a low stone wall and as a squad of five soldiers approached, he quickly stood up and promptly shot one with his musket, another with one pistol, then a third with his other pistol. By then, the British were at point blank range and shot Samuel in the face. When he fell to the ground, they struck him on the head with the butt of a musket and bayoneted him 13 times before leaving him to die.

Four hours later as local townsmen were picking up the American dead, they found Sam lying in a pool of blood—trying to reload his musket! They carried him to a doctor, who pronounced his case hopeless, declaring he would be dead shortly. The family implored the doctor to treat him anyway, so he did what he could before sending Sam home where he could be surrounded by his family as he died.

But to the surprise of all, Sam did not die. In fact, he fully recovered. He had terrible scars but lived another 18 years, carrying to his grave the marks from the wounds he received while fighting for American independence.17 In 1878, a marble tablet was erected near the location where he met the British, with the inscription: “Near this spot Samuel Whittemore, then eighty years old, killed three British soldiers, April 19, 1775. He was shot, bayoneted, beaten, and left for dead, but recovered, and lived to be ninety-eight years of age.”18 Samuel Whittemore is reflective of the committed character of many Americans at that time.

As did many other clergy, on the first anniversary of that event, Rev. Clarke preached a memorial sermon where he declared that he helped train the Minutemen “for that very hour.” He laid out a detailed case for the evidence that the British fired first and the Americans were acting in self-defense.21 This was very important to the colonists because of their belief in “just war.”

John Jay, Founding Father and first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, wrote a long treatise on what biblically constituted a “just war.” In that letter, he stated, “Thus two kinds of justifiable warfare arose: one against domestic malefactors; the other against foreign aggressors. The first being regulated by the law of the land; the second by the law of nations; and both consistently with the moral law.”

It was this studied belief in “just war” and not revolting without cause that led the colonists to the conclusion that their actions in response to Great Britain’s violations of liberty were justified.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1818), 123, speech on March 23, 1775.

- The London Chronicle (June 15-June 17, 1775), Vol. XXXVII, No. 2890, 2, excerpts from a letter by a member of the British Army noting orders were given to “seize…the bodies of Mess. Hancock and Adams, who were both attainted and were at that place enforcing by all their influence the rebellious spirit of the Provincial Congress.”

- J.T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 79.

- Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon, Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776. To Commemorate the Murder, Bloodshed and Commencement of Hostilities Between Great-Britain and America in that Town, by a Brigade of Troops of George III under Command of Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, on the Nineteen of April 1775. To Which is Added A Brief Narrative of the Principal Transactions of That Day (Boston: Powers and Willis, 1776), 5, “A Narrative & c.,” where he says, “for 800 disciplined troops of Great-Britain, without notice or provocation, to fall upon 60 or 70 undisciplined Americans” [Evans # 14679].

- Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon, Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776. To Commemorate the Murder, Bloodshed and Commencement of Hostilities Between Great-Britain and America in that Town, by a Brigade of Troops of George III under Command of Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, on the Nineteen of April 1775. To Which is Added A Brief Narrative of the Principal Transactions of That Day (Boston: Powers and Willis, 1776), 5, “A Narrative & c.,” where he says, “for 800 disciplined troops of Great-Britain, without notice or provocation, to fall upon 60 or 70 undisciplined Americans” [Evans # 14679]. See also Benson Lossing, A History of the United States for Families and Libraries (New York: Mason Brothers, 1860), 232.

- J.T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 79.

- J.T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 81.

- Governor Jonathan Trumbull, “A Proclamation” (for fasting and prayer), issued on March 22, 1775, to be observed on April 19, 1775 [Evans #13879].

- Governor Jonathan Trumbull, “A Proclamation” (for fasting and prayer), issued on March 22, 1775, to be observed on April 19, 1775 [Evans #13879].

- Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 14:233, s.v. “Parker, John.” See also similar orders given at the battle of Concord: “The Militia officers had given particular caution to their men, on no account, to fire the first shot, but to defend themselves if attacked,” from Paul Allen, A History of the American Revolution; Comprehending All the Principal Events Both in the Field and in the Cabinet(Baltimore: Wm. Wooddy, Jr., 1822), 1:242; also, “The Americans…were immediately put in motion with orders not to give the first fire,” from Thomas Y. Rhoads, The Battle-Fields of the Revolution (Philadelphia: John E. Potter & Co., 1854), 50.

- Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776…To Which is Added a Brief Narrative of the Principle Transactions of That Day (Massachusetts: Powars & Willis, 1776), 4, “A Narrative” [Evans # 14679].

- Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776…To Which is Added a Brief Narrative of the Principle Transactions of That Day (Massachusetts: Powars & Willis, 1776), 4, “A Narrative” [Evans # 14679].

- See, for example, sermons: Jonas Clark, The Fate of Bloodthirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776, to Commemorate the Murder, Bloodshed and Commencement of Hostilities Between Great Britain and America in that Town (Massachusetts: Powers and Willis, 1776) [Evans # 14679]; Jonathan Mayhew, A Discourse Concerning the Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers (Boston: 1750), 44-45 [Evans #6549]]; Peter Powers, Jesus Christ the True King and Head of Government; A Sermon Preached before the General Assembly of the State of Vermont, on the Day of Their First Election, March 12, 1778 at Windsor(Newbury-Port: Printed by John Michael, 1778), 26 [Evans # 16019]. Also see statements by political leaders: John Quincy Adams, An Address Delivered at the Request of the Committee of Arrangements for the Celebrating the Anniversary of Independence at the City of Washington on the Fourth of July 1821 upon the Occasion of Reading The Declaration of Independence (Washington DC: Davis and Force, 1821), 26; Samuel Adams, The Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 4:84, “Manifesto of the Continental Congress” on October 30, 1778; Francis Hopkinson, The Miscellaneous Essays and Occasional Writings of Francis Hopkinson, Esq. (Philadelphia: T. Dobson, 1792), 1:111-115, “A Political Catechism,” 1777; James Wilson, The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, ed. Bird Wilson (Philadelphia: Bronson and Chauncey, 1804), 2:496-497; John Witherspoon, The Works of the Rev. John Witherspoon (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1801), 4:166-167, “The Druid: Number III,” 1781.

- Some academics have argued that the War for Independence was unBiblical and unjust. See, for instance, Gregg Frazer, “The American Revolution: Not a Just War,” Journal of Military Ethics 14 (2015), 35-56. However, the authors of this book hold an opposite position and for the reasons offered in this section of Chapter 7 (and because of many other writings by noted theologians of that day and earlier on when Biblical civil disobedience and resistance in self-defense is justified), we believe that the patriots’ resistance to Great Britain was both Biblical and just. Eric Patterson and Nathan Gill affirm this position in “The Declaration of the United Colonies: America’s First Just War,” Journal of Military Ethics 14 (2015), 7-34. See also The Founders Bible (Newbury Park, CA: Shiloh Road, 2017), Romans 13:1-7, “Rebellion or Rightful Overthrow?”; and David Barton, “The American Revolution: Was it an Act of Biblical Rebellion,” WallBuilders (December 29, 2016), accessed on May 25, 2020, wallbuilders.com/american-revolution-act-biblical-rebellion/.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1864), 7:299.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1864), 7:307-308.

- The Liberty Tree and Valley Compatriot Newsletter (February 1997), Donald N. Moran, “Never Too Old: The Story of Captain Samuel Whittemore”; Benjamin and William R. Cutter, History of the Town of Arlington, Massachusetts. Formerly the Second Precinct in Cambridge or District of Menotomy, Afterward the Town of West Cambridge (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1880), 75-77; Samuel Whittemore, Columbian Centinel(February 6, 1793).

- “Samuel Whittemore,” The Historical Marker Database, accessed on May 25, 2020, www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=18142.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia: James Webster, 1817), 140-145.

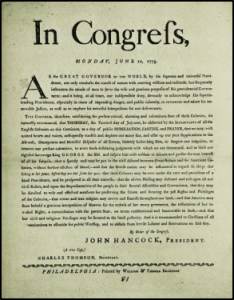

- Journals of The Continental Congress (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1905), 2:87-88, June 12, 1775 (a day of humiliation, fasting, and prayer).

- Sermon – Battle of Lexington – 1776 (at: https://wallbuilders.com/sermon-battle-of-lexington-1776/)