1.1 – The Dawning of Independence

Before reading about the conflicts that led to America forming a new government, watch the following episode of Chasing American Legends for a better understanding of why leaders like George Washington responded as they did.

The Friction Begins…

Fast-forward to 1763 and we find The Treaty of Paris ending The French and Indian War.1 This conflict between the French and the British was known outside of the colonies as the 7 Years’ War. Although Indian tribes fought on both sides of the conflict, the people in the colonies names the war after who they were fighting – the French and certain Indian tribes allied with the French.

With the French defeat, the British won possession of all former French claims in North America, which went westward from the colonies along the east coast to the mighty Mississippi River, north into Canada, and then south to the Gulf of Mexico.2 Though this land gain should have opened up the entire eastern half of the continent to the American colonists, the British drew a line in the sand for settlements at the Appalachian Mountains. Settlers were not to go beyond this line to the west. They set these boundaries because their military forces were spread too thin to protect settlers from probable Indian troubles.3 But this boundary line did not sit well with the expansion-minded colonists who saw many opportunities on the west side of the Appalachians. In fact, we will find a steady stream of frontiersmen ignoring the Appalachian Mountain line and setting up camps along the Ohio River Valley.

Prior to the French and Indian War, the British Parliament began levying restrictions on the colonies through Navigation Laws that required British ships to carry all commerce to and from the colonies.4 These Navigation Laws were designed to keep the profit of trading within the British Empire and resulted in Americans losing out on a lot of potential profit to the British. In essence, the Navigation Laws were a government controlled monopoly that went completely against the free market principles that the colonists believed in. At the end of the war, the Parliament needed to refill its depleted royal treasury. In early 1764, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer (the head of the royal treasury) presented his American Revenue Act, known on our side of the ocean as the Sugar Act. This Act increased taxes on a large number of commodities, and even banned the importation of certain products, such as French wines and rum. These taxes, done without any input from the colonists, were a source of great frustration. Then, adding to the colonists’ anxiety, was an act to revitalize the royal customs collections service, which was only collecting about a quarter of what it needed to operate.5 This fact resulted in deficits that the British government wanted to fix. To add insult to injury, the Parliament came to the conclusion that the colonials should bear the lion’s share of the cost to keep military forces in the colonies.6 This sparked even more outrage due to the fact that the colonists, with their local militias, did not see a need for these British troops. The colonists were largely used to maintaining their own defense through their local militias.

Without representation in Parliament, the colonists strongly opposed all of these measures and began the mantra of “no taxation without representation.”7 In response to these new edicts, the Massachusetts colonial legislature established a Committee of Correspondence and invited the other colonies to join with them. These Committees of Correspondence were designed to educate the colonists and promote communication throughout the colonies. Through this exchange of information, they were able to protest the new restrictions, taxes, and injustices by beginning a series of boycotts of selected English goods.8

The courts became another sore spot for the colonists when the British Parliament established a new vice-admiralty court, located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to have jurisdiction over all the American colonies. The system was full of grave injustices, such as, all cases were to be tried at this one location, before a panel of military officers instead of a jury of peers; the accused person was required to prove innocence rather than the government prove guilt; and the accused had to post bond to pay for costs of litigation.9 So many of these things end up being specific complaints of the American Founders in the Declaration of Independence and then they specifically prevent these abuses in the American Constitution. But just wait! The list gets longer.

1765 brought even more agitation as Parliament passed two more egregious acts affecting the colonies. First, the Quartering Act, which required the colonists to provide supplies and housing for the British troops in public buildings, private buildings, and even private homes.10 Second, the Stamp Act, which had nothing to do with postage stamps, required all paper documents to carry a special stamp showing that a tax was paid on the items. Because this tax applied to every legal document, newspaper, almanac, and shipping document, even playing cards, its economic impact was felt in every colony at every level.11

Colonists Begin to Push Back

Secret organizations arose in many communities, often using the name “The Sons of Liberty,” to challenge enforcement of the new laws.12 Tax collectors were sometimes harassed until they resigned their official positions, some were tarred and feathered, and even homes of a few government officials were ransacked.13 Boycotts of English goods were organized through the strong communication lines that were the Committees of Correspondence, and encouraged by many prominent leaders in Massachusetts and resolutions written by Patrick Henry and narrowly adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses.14 The backlash from the colonies forced the government in England to take action. The Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, largely at the insistence of British merchants hurt by the boycotts. However, its repeal was followed the same day by the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had “binding authority” (absolute power) over the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”15 Obviously, this restriction of colonial autonomy was yet another straw on the camel’s back that was getting ready to break.

Secret organizations arose in many communities, often using the name “The Sons of Liberty,” to challenge enforcement of the new laws.12 Tax collectors were sometimes harassed until they resigned their official positions, some were tarred and feathered, and even homes of a few government officials were ransacked.13 Boycotts of English goods were organized through the strong communication lines that were the Committees of Correspondence, and encouraged by many prominent leaders in Massachusetts and resolutions written by Patrick Henry and narrowly adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses.14 The backlash from the colonies forced the government in England to take action. The Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, largely at the insistence of British merchants hurt by the boycotts. However, its repeal was followed the same day by the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament had “binding authority” (absolute power) over the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”15 Obviously, this restriction of colonial autonomy was yet another straw on the camel’s back that was getting ready to break.

In 1767, we find Charles Townshend as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. After he got the Parliament to pass legislation reducing land taxes in England, he immediately asked the Parliament to pass laws aimed at shifting the tax burden to the colonies. Known as the Townshend Acts, he asked for new duties (taxes) on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea imported into the colonies. He also abused his authority by allowing customs officials to issue writs of assistance.16 What is a writ of assistance? It basically authorized local judges to issue open-ended search warrants that did not specify the objects or places of the search and the writs never expired.17 These writs of assistance were especially egregious to the colonists. Officials could go into any home or business, anytime they wished, and search for anything they wanted. For example, John Hancock’s merchant ship, the Liberty, off-loaded a cargo of wine without paying customs, and was then seized by the British navy using one of these writs of assistance.18

As these usurpations continued, customs officials began formally requesting troops be quartered in Boston for their own protection.19 Pressure continued to mount when the New York Colony’s boycott of British goods resulted in minor riots in that city. When the New York colonial legislature refused to pay for the quartering of British troops, the London Board of Trade, which still supervised all activity in the American colonies, declared all acts of the NY legislature null and void.20

As we move two years forward in this historic timeline, 1769 proved to be a pivotal year in the colonies. Tensions were so high between the colonists and British officials that the Virginia House of Burgesses (the state legislature for Virginia) unanimously adopted resolutions declaring the sole right to tax the colonists lay with the governor and legislatures of each colony. The resolutions also included condemnation of the proposal that “American” troublemakers be tried in England, demanding they be tried in the colony in which they reside. The names affixed read like a Who’s Who among American Founders (George Washington, Patrick Henry, George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, Carter Braxton, Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, and many others).21 The royal governor immediately dissolved the Virginia assembly.22 The impact of his abuse of power? Other colonies followed Virginia’s lead with resolutions of their own.23 And this would not be the last time that British authorities unilaterally dissolved American elected assemblies. These actions led to increased boycotts of British goods across the colonies. In fact, New York decreased import of British goods by almost eighty-five percent.24 The response from England’s new Prime Minister, Lord Frederick North, was to repeal almost all of the import duties/taxes. But in an effort to remind the colonists that Parliament still had authority “in all cases whatsoever,” he kept the tax on tea.25

Bloodshed Begins…

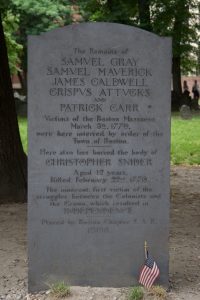

We now turn our attention to a critical event that illustrates the severity of the tensions. As background, it is important to note that the British troops quartered in the colonies were not known to have the best of character. They had little respect for the colonists, and were often drawn from Britain’s lower class. The arrogance of these soldiers brought about continuous heckling from the Americans.26 In March 1770, a crowd was heckling a lone British sentry at his Customs House post. When he called for help, a detachment of soldiers came to the scene, shots were fired and five American men were killed. One of the first to fall was Crispus Attucks, a free Black man from Boston.27 Newspapers throughout the colonies quickly painted this incident as The Boston Massacre.

Another incident of hostility followed in June 1772. A British customs ship, the HMS Gaspee, was in pursuit of a probable smuggler ship (a free merchant ship that was not following the British Navigation Laws) in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. The smugglers appeared to deliberately lead the customs vessel into shallow waters where it ran aground. That night, several boatloads of “unknown persons” completely destroyed the ship by setting it on fire. Upon investigation of the Gaspee Incident, the British found no one willing to admit to having any information whatsoever. The British reacted to the silence by announcing that anyone involved in the incident would be tried in England, and henceforth, all judges would be paid directly from the British treasury and not from local taxes.28 This would mean no local accountability for judges, which colonists knew was a formula for abuse. The Gaspee Incident also brought about a resurgence of the Committees of Correspondence for disseminating important information about British abuses of power throughout the colonies.29 This relatively good communication network had the effect of unifying the colonies in a new way.

As the flames of discontent and a desire for freedom continued to rise in the colonies, the East India Company (the British merchant consortium responsible for trade with the new British colony in India) was in serious financial trouble because of the American boycotts on tea. In May of 1773, with seventeen million pounds of tea in English storehouses and little market for it, the East India Company convinced Parliament to remove duties on tea in the home country of England, but leave a tax of three pence per pound of tea on the American colonies.30 The Americans detested this interference with free trade. Since many colonists considered themselves full Englishmen, this blatant favoritism to England at the expense of the American colonies was considered yet another injustice toward the colonists.

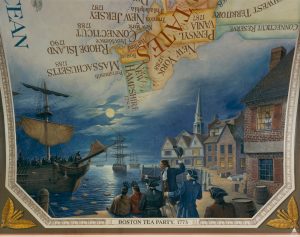

The Original Tea Party

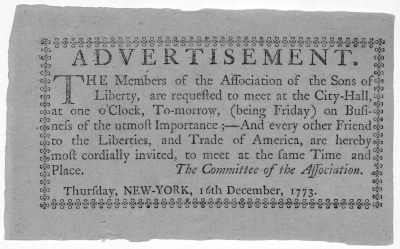

A short ride in our time machine brings us face to face with the inevitable conflict between the colonists and East India Company in December 1773, which the colonists viewed as representative of British controls on the free market. An East India Company ship, the Dartmouth, arrived in Boston with a load of tea. The citizens of the city held public meetings and demanded that the ship leave without unloading its cargo.31 The Massachusetts royal governor demanded that the tea be unloaded, but during the night of December 16, a group of men, led by the Sons of Liberty, some disguised as Mohawk Indians to protect their identities, boarded the ship and threw 342 chests of tea into the Boston harbor as an act of protest against the unjust policies that England was enacting on the colonies. Nothing else on the ship was damaged. In fact, the Sons of Liberty went out of their way to clean up and not damage the ship.32 This incident later came to be known as the Boston Tea Party. Similar “parties” took place during the next few months in New York, New Jersey, and Maryland.33

The chess match continued with the British passing the Boston Port Bill in 1774, which closed the port of Boston to all shipping until the tea and its customs duties were paid in full.34 This was soon followed by the Massachusetts Government Act, which basically annulled the colonial charter, leaving the royal appointed governor in complete control of the legislature, law enforcement, and judiciary.35 As a result, the people and the colonial elected officials completely lost their voice in public policy matters.

The new Quartering Act was parliament’s next move, authorizing quartering British troops in private, occupied homes of average citizens. (Just imagine the government forcing your family to open your home to strange men, agents of a government antagonistic to your family, and sleeping and eating under your roof.)36 How much resentment do you think this would build up in your family? Parliament then passed the Quebec Act, which defined Canada’s boundaries as extending southward to the Ohio River. This was intolerable to the people of Virginia, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, all of whom had claims to parts of the Ohio River Valley.37

Next move, Virginia. A small group of delegates to the House of Burgesses, including Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and Richard Henry Lee, met to discuss the public apathy about their deteriorating freedoms. They agreed to call for a day of prayer, humiliation and fasting before God, and sent letters to all the colonial Committees of Correspondence, asking them to join in this public expression of faith. Thomas Jefferson penned the resolve in Virginia “to implore the Divine Interposition…to give us one heart and one mind firmly to oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American rights.”38

What day did they choose to fast and pray? The day the Boston Port Bill was to go into effect!39

Congress Assembled… in prayer?

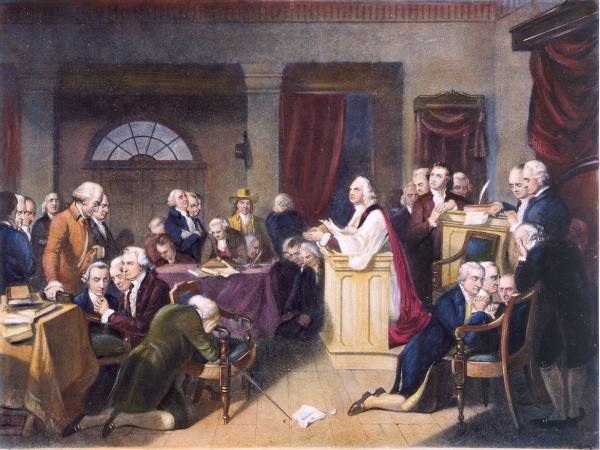

We discover that 1774 brought a shift in action throughout the colonies. That summer, twelve of the colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress.40 This gathering was the first significant join national assembly with many of the same men who would later lead in the birth of the new nation. Unsurprisingly, they began the historic gathering with an extended time of prayer and Bible study. Congress then passed several resolutions directed to the colonists in which they: (1) condemned what they called Coercive Acts of Parliament (the group name for all of the recent acts that Parliament had passed to restrict and punish the colonies, also called the Intolerable Acts) as intolerable, and therefore not to be obeyed; (2) urged the people of Massachusetts to form a government to collect taxes, but withhold them from the royal governor until the Coercive Acts were repealed; (3) advised the people throughout the colonies to form armed militias for their own protection; and (4) recommended increased restrictions on trade with England.41

This First Continental Congress also passed two other resolutions directed to the king. They first protested the Quebec Act as unjust. Among other things, this Act expanded the territory of Quebec into what was previously Ohio territory, restored the limited use of French civil law in private law, and restored the Catholic Church’s ability to forcefully impose tithes.

Later, in the Declaration of Independence, the colonists would enumerate their problems with the Quebec Act by saying that it was “…abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies…”

The second resolution passed by Congress petitioned the king to end the Coercive Acts; but the American colonists still pledged loyalty to him.42 It is hard for us to imagine it today, but at that time, we must understand that a vast majority of colonists still considered themselves loyal subjects to the king. Many believed he was only being misled by his court and parliament. The Congress decided to meet again in May, 1775, if the response from Britain was not acceptable.43

The British response was mixed at best. The Prime Minister, Lord North, introduced legislation in the House of Lords calling for official recognition of the Continental Congress, granting it limited powers to set taxes in the colonies, but the Parliament rejected his plan. Instead, it officially declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion.44 A month later, the king permitted Lord North to work a plan of reconciliation on the same day Parliament passed the New England Restraining Act, forbiding the New England colonies (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire) from trading with any nation other than Britain and its Caribbean colonies. It also barred the New Englanders from using the North Atlantic fishing grounds.45 The Act was later expanded to five additional American colonies.46

- Office of the Historian, “Treaty of Paris, 1763,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris) (accessed on March 1, 2017). See also George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, pp. 451-454 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=481).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, p. 452 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=482). See also “The Treaty of Paris (1763) and its Impact,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/8d.asp) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 163-168 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=179). See also “British Reforms and Colonial Resistance, 1763-1766,” Library of Congress (at: https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/amrev/britref/) (accesse on March 1, 2017). Read the original proclamation setting these boundaries from The London Gazette dated October 4 to October 8, 1763 (at: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/10354/page/1).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. II, pp. 42-48 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4w9h;view=1up;seq=60). See also “Navigation Acts,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Navigation-Acts) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 187-189 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=204). See also “1764 – Sugar Act,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/sugar-act/1764-april-5-sugar-act/).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, p. 186 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=202).

- See, for example, William Pope Hazard, The American Guide Book (Philadelphia: George S. Appleton, 1846), Part 1, p. 34 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=HFVKAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA34#v=onepage&q&f=false); “No Taxation Without Representation,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/headline/no-taxation-without-representation-2/) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles A. Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, From the Discovery of the Continent by Christopher Columbus to the Present Time (Hartford: J. Seymour Brown, 1842), pp. 213-214 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=3F49AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA213#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- Hampton L. Carson, The History of the Supreme Court of the United States (Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler, 1902), Vol. I, pp. 29-35 (at: https://books.google.com/books?

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 201 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=227). See also “Quartering Act,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Quartering-Act) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles Botta, History of the United States of America (London: A. Fullarton & Co., 1850), Vol. II, pp. 29-33 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=u9FSAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA29#v=onepage&q&f=false). See also “1765 – Stamp Act,” stamp-act-history.com (at: https://www.stamp-act-history.com/stamp-act/1765-november-1-stamp-act/) (accessed on March 1, 2017).

- Charles A. Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, From the Discovery of the Continent by Christopher Columbus to the Present Time (Hartford: J. Seymour Brown, 1842), pp. 204-205 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=3F49AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA204#v=onepage&q&f=false). See also “Sons of the Liberty,” Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum (at: https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/sons-of-liberty) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 308-321 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=324). See also “The Stamp Act Riots,” History, August 14, 2015 (at: https://www.history.com/news/the-stamp-act-riots-250-years-ago).

- See, for example, George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 274-278 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=290); “New York Merchants Non-importation Agreement; October 31, 1765,” The Avalon Project (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/newyork_non_importation_1765.asp); “The Stamp Act Controversy,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/9b.asp) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. V, pp. 434-437, 445 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtkf;view=1up;seq=450); “The Declatory Act, March 18, 1766,” Constitution Society (at: https://www.constitution.org/bcp/decl_act.htm).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 76-80 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=102). See also “The Townshend Acts,” Massachusetts Historical Society (at: https://www.masshist.org/revolution/townshend.php) (accessed on March 2, 2017); “Townshend Acts,” Encyclopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Townshend-Acts) (accessed on March 2, 2017).

- “Writs of Assistance: 1761-72,” The Founders Constitution (at: https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendIVs2.html), quoting from Quincy’s Rep. (Mass.).

- Fore more information, see an “Editorial Note” in the online collection of Legal Papers of John Adams, Volume 2 (at: https://www.masshist.org/publications/apde2/view?id=ADMS-05-02-02-0006-0004-0001).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 136 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=162).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 76, 274 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=274).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 279-281 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=305). See also “The Virginia Resolves of 1769,” TeachingAmericanHistory.org (at: https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/the-virginia-resolves-of-1769/) (accessed on March 7, 2017); “Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions, 17 May 1769,” National Archives (at: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0019).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 281 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=307).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 281-282 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=307).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 365 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=391)

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 350-354 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=376).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 332-335 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=358).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 336-341 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=362).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 416-418, 441 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=442). See also “Gaspee Virtual Archives” gaspee.org (at: https://www.gaspee.org/) (accessed on March 7, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 428, 444-445, 454-455 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=454).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 457-459 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=483). See also “Significance of the Tea Act, 1773,” Boston Tea Party Historical Society (at: https://www.boston-tea-party.org/tea-act.html) (accessed on March 7, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 477-483 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=503). See also “The Story of the Boston Tea Party Ships,” Boston Tea Party Historical Society (at: https://www.boston-tea-party.org/darthmouth.html) (accessed on March 13, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, pp. 484-487 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=510). See also records of participants and other historic accounts

from the Boston Tea Party Historical Society: https://www.boston-tea-party.org/accounts.html.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. VI, p. 525 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wav;view=1up;seq=551); Vol. VII, pp. 142-143 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=154); Bessie Ayers Andrews, Historical Sketches of Greenwich in Old Cohansey (Vineland, NJ: Vineland Printing House, 1905), pp. 42-45 (at: https://books.google.com/books?id=_ok-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA42#v=onepage&q&f=false).

- “Boston Port Act: March 31, 1774” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/bpb.html).

- “Massachusetts Government Act: May 20, 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/mga.html).

- “Quartering Act of 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/q74.html).

- “Quebec Act: June 22, 1774,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/cqa.html); “The Intolerable Acts,” ushistory.org (at: https://www.ushistory.org/us/9g.asp).

- From a reprint of a Proclamation of the Virginia House of Burgesses for a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer on the 1st Day of June, Tuesday, the 24th of May, 14 GEO. III 1774.

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 52-53 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=64).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 127-134 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=139). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 139-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=150). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 146-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=158).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 149-150 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=161). See also Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress, 1774-1781,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress) (acccessed on March 15, 2017).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, pp. 217-227 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=229).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1858), Vol. VII, p. 239 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn4wau;view=1up;seq=251); The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the end of the Elventh Parliament of Great Britain (Cambridge: John Archdeacon, 1775), Vol. XXXI, pp. 4-11, “An act to restrain the trade and commerce of the provinces of Massachusett’s Bay and New Hampshire, and colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island and Providence Plantation in North America, to Great Britain, Ireland, and the British islands in the West Indies” (at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B09RAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA4=onepage&q&f=false)

- The Statutes at Large, from Magna Charta to the end of the Elventh Parliament of Great Britain (Cambridge: John Archdeacon, 1775), Vol. XXXI, pp. 37-43, “An act to restrain the trade and commerce of the colonies of New Jersey, Philadelphia, Mayland, Virginia, and South Carolina, to Great Britain, Ireland, and the British islands in the West Indies, under certain conditions and limitations” (at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B09RAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA37=onepage&q&f=false).