Chapter 1 – Movements Leading to Independence (Overview)

Understanding What Led To The American Republic

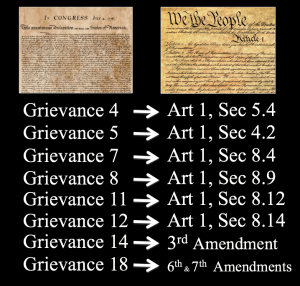

As we walk through the events leading to independence, keep the many abuses and usurpations in mind because you will later see specific measures in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution referring to and preventing a repeat of these abuses.

In order for us to understand our system of American government and it’s extraordinary results, it is necessary to first grasp the series of events that led to the dawning of our nation. Keep in mind these events led to the nation which has provided you with unprecedented freedom, prosperity, and opportunity. If we are going to keep these things alive for future generations, we must understand the systems of government and economics that produce such benefits. To understand what we now have in America, we must take a closer look at how the long train of abuses and usurpations by the British Parliament and king inevitably brought about the War of American Independence. The Declaration of Independence was not the work of a few rebels and malcontents, but rather the result of a growing movement of the people who came to realize their freedoms were being trampled by a despotic government.

Time Travel…

Rather than just memorizing dates and names, let’s take a time machine trip back to the dawning of independence and walk through the experiences of the Founding Fathers of the American system of government. Imagine whatever mode of time travel you would like, but let’s arrive together in the early 1750s. We begin by witnessing a series of official changes in the way the King of England and his government managed their colonies on the North American continent in the latter part of the 18th century. The greatest change was the revocation of “mercantile charters” in favor of “royal charters,”1 which then gave the king the authority to appoint his own governors, judges, and customs officials. Under a mercantile charter, the king would grant authority to groups of private capitol investors who would then conduct the business of the colony or area. However, under a royal charter, a governor (appointed by the Crown) administered the affairs of the area or colony. The mercantile charters created what came to be known as “charter colonies” in America that has a large degree of autonomy. The royal charters, on the other hand, created “royal colonies” or “crown colonies” that were very dependent on the king for their government. During this time, the king revoked several mercantile charters and replaced them with royal charters, consolidating his authority and power in the American colonies.

The Board of Trade in London was originally created to manage the fur trade, fisheries, and shipping interests.2 However, after a time the Board of Trade made most of the colonial governmental appointments in the name of the king. As you might imagine, there was constant friction between the royally “appointed officials,” (who were not elected by the colonial residents) too often owing their allegiance to the king, and the colonial landowners and businessmen, who believed they were more than capable of handling their own businesses and government.

What A Great Idea!

Needless to say, this lack of local representation, feeling like a far-away king was making law without any local input, created a major amount of friction between the colonies and the king. On top of that, there was also great friction between the French and British over rights to trade with the American Indian tribes, as well as their continuous disputes over claims to the same land areas. The British held claim to most of what we would recognize today as the East Coast of the U.S. while the French still held claim to Canada and what would eventually become the Louisiana Purchase. The large shared border was constantly under dispute. In 1754, this friction led to war between the French and British, known in America as the French & Indian War.3 This war saw battles on the American continent and in other areas too and as you can imagine, required heavy financial commitments from both royal courts, and brought about a very interesting unintended consequence. To ensure the aid of the colonies, the British authorities requested a “Congress of Representatives” of the northern and middle colonies gather together to establish a united plan of action to counter the French.4

One of the congressional delegates, Benjamin Franklin, had written a “Plan of Union” for the colonies, but it had never gotten much exposure beyond his circle of friends. Then in June of 1754 at Albany, New York, drawing on Franklin’s earlier plan, the Albany Plan of Union was accepted by the congress but ultimately rejected by all of the British-run colonial governments as too bold a step in the face of their differing colonial economies and cultures.5 The seed of the idea, however, was now planted. Though the king wanted the “Congress” to establish a united plan to counter the French, the Albany Plan was actually the first significant attempt at unifying the colonies into one national entity.

It was during the French & Indian War that George Washington rose to national prominence through his courageous leadership and miraculous survival at the Battle of the Monongahela in July, 1755. Watch this video, BulletProof President?, for a hilarious, yet informative investigation into this famous battle.

- The Avalon Project through Yale Law School has an extensive list of colonial charters. Jut a few examples are: “Charter of the Dutch West India Company: 1621,” The Avalon Project, charter dated June 3, 1621 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/westind.asp); “Charter of Connecticut – 1662,” The Avalon Project, charter dated April 23, 1662 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ct03.asp).

- The Avalon Project through Yale Law School has an extensive list of colonial charters. Jut a few examples are: “Charter of the Dutch West India Company: 1621,” The Avalon Project, charter dated June 3, 1621 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/westind.asp); “Charter of Connecticut – 1662,” The Avalon Project, charter dated April 23, 1662 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ct03.asp).

- For an overview of this war, called “The French & Indian War” in America and “The Seven Years’ War” in Europe, see: “French and Indian War,” Encylopedia Britannica (at: https://www.britannica.com/event/French-and-Indian-War) (accessed on February 23, 2017). And for a more detailed overview of this war in America, see George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, passim (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=11).

- George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, p. 121 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=141).

- Office of the Historian, “Albany Plan of Union, 1754,” Department of State (at: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/albany-plan) (accessed on February 23, 2017); George Bancroft, History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1852), Vol. IV, pp. 123-126 (at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hnjtke;view=1up;seq=143).